Six Things is a year old.

To celebrate, I’m giving away a copy of Taking Flight (but not just any old copy – see below).

To enter, you need to:

– be a free subscriber to Six Things. If you’re not already, you can do that here.

– email your own Six Things to me

That’s all! It’s simplicity itself.

Entries close at 23.59 (UK time) on Saturday 25th November 2023.

Here’s the small print:

– the copy of Taking Flight will not only be signed and dedicated (if you want), it will be annotated by me. Expect comments like "we should have cut this bit", "this paragraph doesn’t make sense", "this is factually incorrect", and a series of random margin doodles, as well as pathetic attempts to illustrate some of the featured flyers.

– your Six Things can be as short or long as you like. It might just be six favourite words, six useful household items, six colours you really really like. Or you might push the boat out and decide to do six 1,500-word essays on your favourite 19th-century Italian operas. Or you might follow my template and just send six things you’ve enjoyed in the last week, with or without commentary.

The winner will be no more and no less than the entry I like the most.

Now that’s done, let’s get to the Things. Nostalgically, selfishly, and just a bit lazily, this anniversary edition of Six Things is just a collection of six of my favourite things of the last year. If you’re a veteran subscriber, hope you enjoy revisiting them; if you’re new, this is the kind of thing you’re in for. If you have your own favourites, do let me know.

(This post is rather long, so might not load fully in the inboxes of email subscribers. But you can click on any of the links to access the web version.)

Thing 1 – Migration Atlas

All the way from Volume 2. This subject fascinates me more and more with each passing day.

The more you learn, the more you realise how little you know.

Take bird migration, with its apparently unending mysteries. How do they do it? Why? When? Where? How far?

You may as well ask the length of a piece of string. Migration is the broadest of churches. Some spend their entire lives on the move; for others it’s just a case of going up or down a hill.

If it’s astonishing feats of aerial endurance you’re after, look no further than the bar-tailed godwit, members of which species seem to delight in breaking each other’s records by small margins on an annual basis, like so many avian Sergei Bubkas. Here’s the latest, a staggering 11-day non-stop journey undertaken by a juvenile bird – named, rather unimaginatively, ‘B6’ – at an average of just over 50 kmh.

That’s 50 kilometres every hour, for just over eleven days, without stopping. It’s exhausting just thinking about it.

As a young birder I learned about the basic rhythms of migration. In the UK this means we get summer visitors from the south (the most obvious and glamorous are probably the swifts, swallows and martins that delight us with their aerial activities through the dog days of July and August), and winter visitors from the north (think straggling arrowhead formations of geese or the thousands upon thousands of waders that perform extreme aerobatic team routines at high tide through the winter over the mudflats of Norfolk).

But those migrations, arresting and romantic as they are – such tiny things, such huge distances – make up just part of the story. Because birds are on the move all the time. And sometimes the identity of the movers is unexpected.

Take the robin. The gardener’s friend, staple of Christmas cards, one of our commonest residents (also, as you might know, possessed of extraordinary aggression towards anyone or anything that dares encroach on what they regard as their territory).

Robins stay put, right? Those same two birds have been coming to the feeder these past six years. We’ve seen them.

Up to a point.

Inconveniently for that narrative, robins have a life expectancy of about two years. So that ‘same robin’ you’ve been feeding all that time will more likely be a succession of them.

But it also turns out that while a good chunk of the robin population does stay put, another chunk is decidedly mobile.

The Migration Atlas, launched earlier this year, brings together over a century of bird ringing records with the latest satellite tracking data to build interactive maps of the movements of over 300 bird species.

It’s quite addictive.

Here’s the map of robin movements – each line is a single bird, ringed or satellite tracked at some point in the last 100 years or so, and then caught again and diligently logged. Safe to say they’re not all just hopping down the road because you get a better class of mealworm at number 68.

You can pick pretty much any bird, and the extent to which populations are on the move at various times of the year makes you blink. Here’s the blackbird, for example. Even the blue tits are at it.

And then you look at the proper long-distance migrants and you have to have a bit of a sit-down. This is what swallows do.

Once you start thinking about it – journeys all over the place, fraught with danger – and start to visualise the reality of it – very small birds, very large distances – it becomes not just astonishing, but deeply moving too, and triggers all sorts of thoughts about the extraordinary fragility and resilience of life.

If bird migration interests you, I can thoroughly recommend Ian Newton’s Bird Migration for an in-depth exploration of the subject. Less exhaustive, but no less fascinating, is Scott Weidensaul’s A World On The Wing.

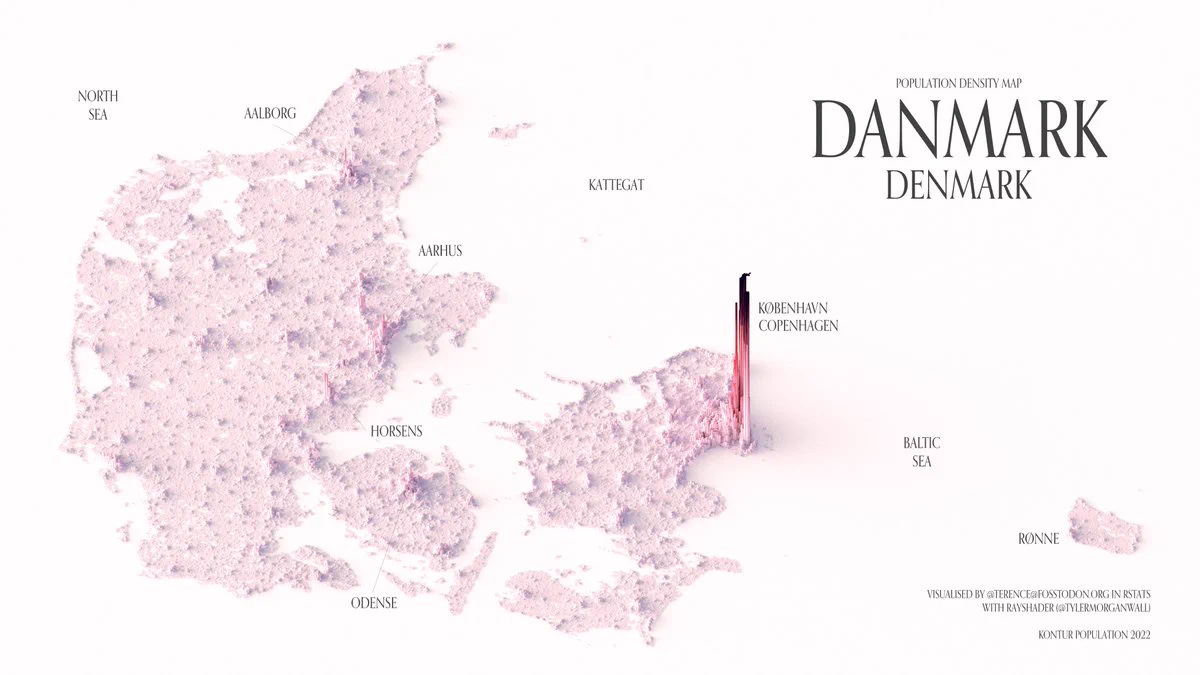

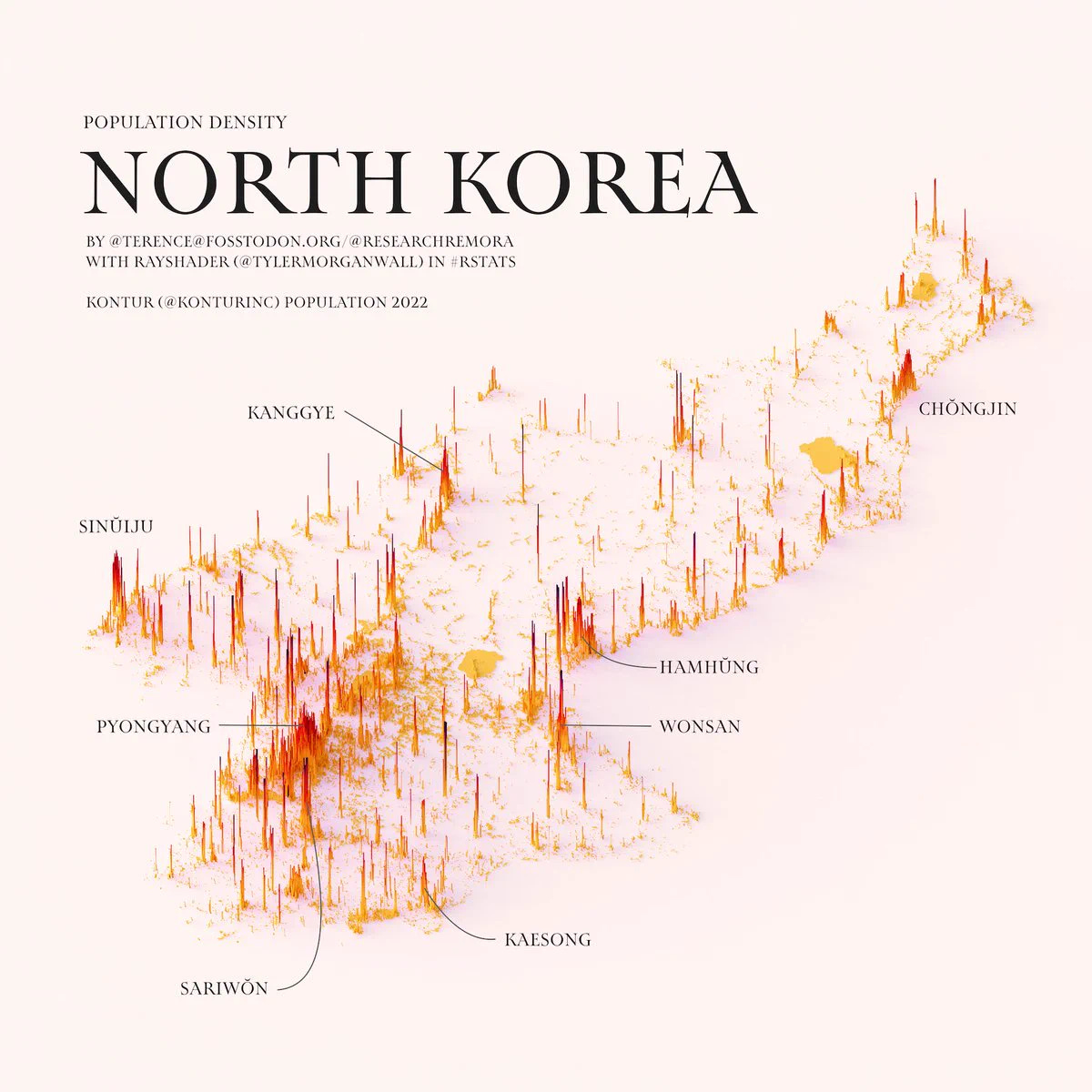

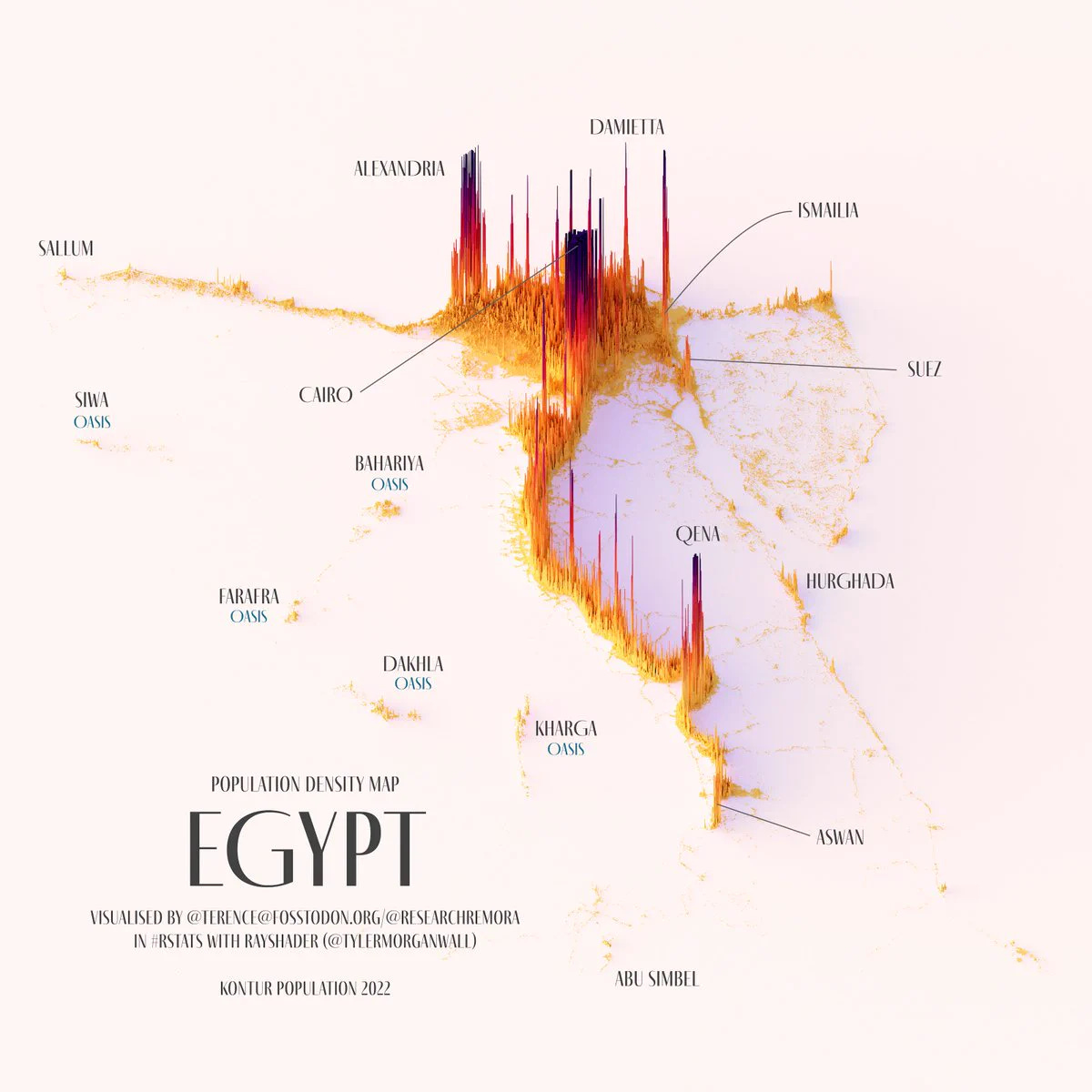

Thing 2 – Population Maps

These population maps from Volume 35 are so nicely done, I had to include them.

I like a map. And I particularly like one that presents data in an interesting, informative, and frankly pretty way.

So these maps of population density – which show very effectively just how full or empty some places are – are very much the kind of thing for which I’m prepared to put my hands together repeatedly and make a sort of appreciative slapping sound.

In short, I applaud them.

They’re the work of Terence T (@researchremora on Twitter)

Thing 3 – Merlin

This piece about the Merlin app, from Volume 16, proved one of the most popular Things of the year.

“Oh, you must try Merlin. It’s amazing!”

“I love Merlin!”

“I don’t know how I managed without Merlin!”

There comes a time, when people are raving about something, when you decide that you’re never going to succumb. You hold out, a lone voice of sanity in a world gone mad, and wait for the nonsense to die down.

It worked with 24 all those years ago, and it’s working, so far, with Succession.

For the uninitiated, Merlin is a birding app developed by Cornell University. In their words, “identify the birds you see or hear with Merlin Bird ID.”

“Yeah yeah yeah, whatever,” I thought privately (and now not so privately). “If you love Merlin so much why don’t you marry it?”

A large part of this reaction, I admit, is defensiveness. I’ve devoted a fair amount of time over the last few years evangelising about the joys of learning to recognise the songs of birds for yourself, the key tools used in this endeavour being online recordings and lots of practice. There are no shortcuts to learning birdsong – you just bally well have to knuckle down. The last thing I wanted was some newfangled technology making me (in that small niche of my existence, at any rate) redundant.

Turns out there are shortcuts. Or, at the very least, learning aids.

In the end I decided I had to try it. I slightly – only very slightly, mind – wanted it not to work, so I could report back with a partially regretful “oh dear, what a shame, never mind.”

Very mean-spirited of me, I know.

So it is with not a little sheepishness that I report that Merlin is excellent. Actually, not just excellent. Bloody marvellous.

Shall I start with the negatives? Yes. My ego demands it.

Merlin struggles with a few things. It doesn’t like wind much. It doesn’t like faraway birds much. It doesn’t especially like it when they all sing together (although it likes it more than I thought it would). And it has a funny blind spot with certain vocalisations of the Carrion Crow. The West Norwood Carrion Crows, at least.

It failed to recognise (or maybe just didn’t hear) quite a few that were distant, and that an experienced birdlistener would pick up instantly. And just once, when five species were going off all at once, it had a mild hissy fit and refused to recognise the existence of any of them.

But that’s about it, really. It recognised a lot of birds from scant information – just a cheep here or a tsip there. And it sorted out a goldfinch and a blackcap singing simultaneously – I only realised the goldfinch was singing when the blackcap stopped.

For anyone who is interested in birds, wants to learn more about them, and in particular wants help with recognising them by their songs, I recommend it wholeheartedly. And it works, by the way, anywhere in the world.

Here comes the caveat.

I think Merlin works best as an aid to learning. Ideally, you’ll take a bit of time after each session – you can have it listening all the time as you walk – to listen back and build on whatever knowledge you already have. And it does help (although it’s not essential) if you have a little knowledge and are prepared to use your critical faculties when examining the results. Was that really a Common Sandpiper (a small wader and habitué of hill streams, reservoirs, lakes and gravel pits) lurking in the bushes at West Norwood Cemetery? I think not. Did a Lapwing (another wader, known mostly on farmland) grace me with its presence in distinctly un-farmy Regent’s Park on Wednesday? With the best will in the world, no, it did not.

But these are the most minor of complaints.

I would even go so far as to say this: if you have no interest in birds or birdsong (in which case you might not even have read this far), download it and give it a go. You might just enjoy it.

Get it. Use it. Have fun. And tell me what you hear.

There’s a demo of Merlin here.

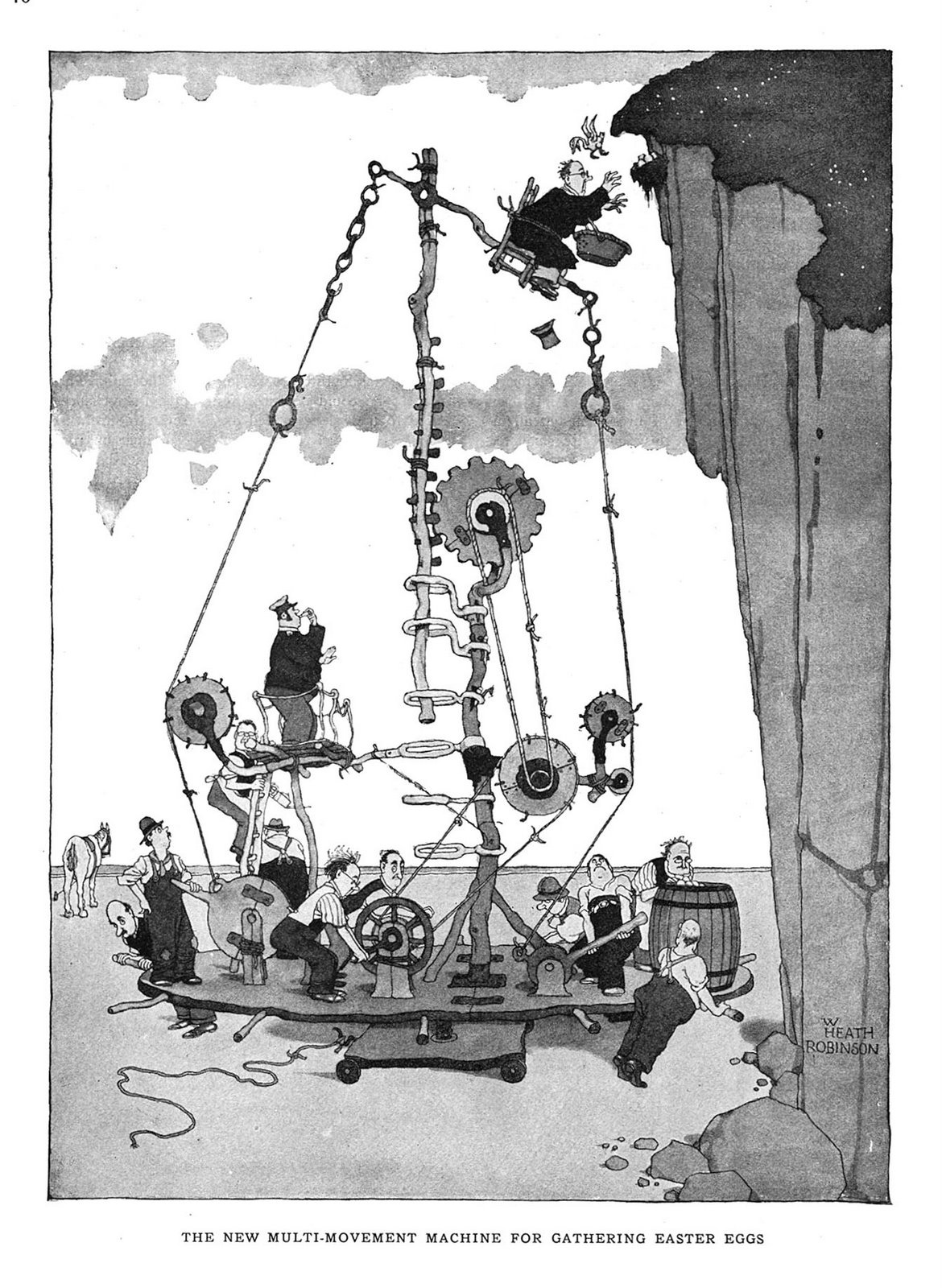

Thing 4 – Rube & Heath

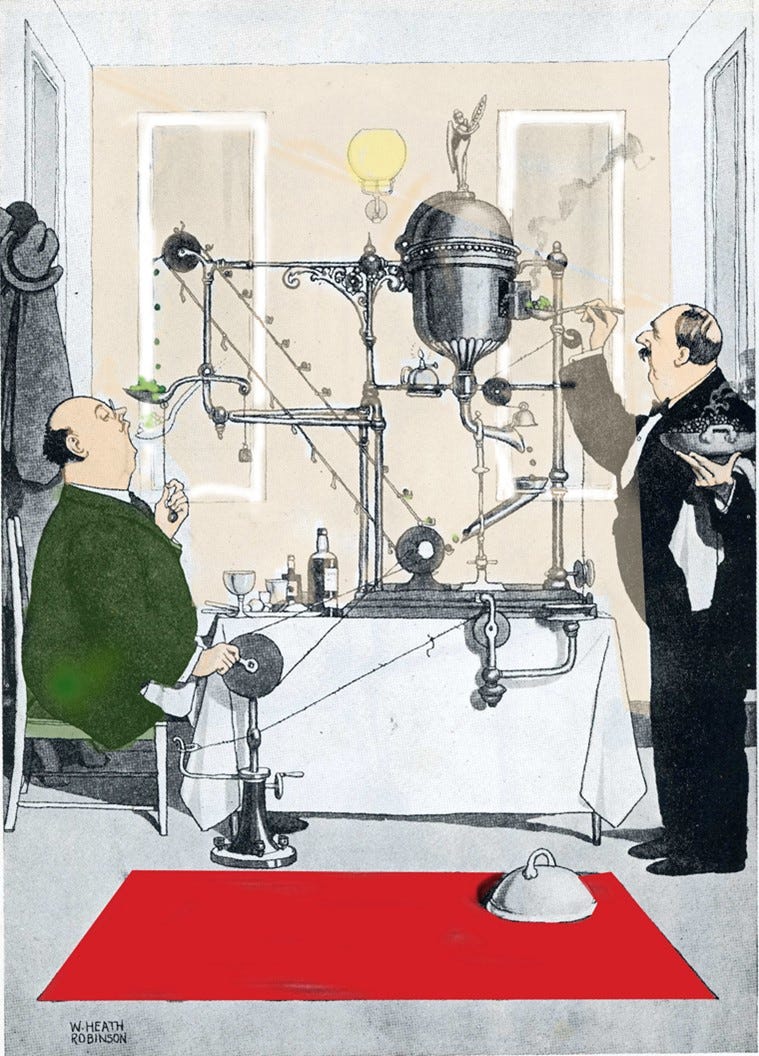

My fascination with Rube Goldberg and Heath Robinson overflowed in Volume 8.

One thing leads to another. And if you were Rube Goldberg, one thing led to another, then another, then another, then another – all delivered with wit and imagination.

I hadn’t heard of Rube Goldberg until 2003, when ‘Cog’ hit the screens.

(It was hailed by Honda as one of the most influential adverts ever made, but then they would say that, wouldn’t they?). It remains, to my eyes, deliciously watchable.

If Goldberg’s name wasn’t familiar, the concept behind his cartoons was, thanks to the work of Heath Robinson – outlandishly elaborate machines designed to complete extremely simple tasks. Or, as Goldberg put it more simply (there’s an irony for you, simplicity not exactly a word associated with his work), “Do an easy thing the hard way.”

Heath Robinson’s contraptions seemed to be the epitome of British eccentricity, clearly constructed in a shed with what was to hand – cogs and wheels, string and tape, pulleys and winches – and often featuring bald middle-aged men snoozing in rocking chairs, blissfully unaware of the precariousness of their situation. As a child I spent hours looking at them, drinking in the details, tracing their mechanisms and imagining them in operation. And I wasn’t the only one. H G Wells, writing to Robinson in 1914, told him, “Your absurd, beautiful drawings … give me a peculiar pleasure of the mind like nothing else in the world.” Discovering Goldberg’s cartoons as an adult, I found they had a similarly homespun charm, and the parallels between the two are easy to draw.

Such machines might seem merely a whimsical celebration of glorious uselessness, but both Goldberg and Robinson drew their cartoons with sharp satirical intent. The 1920s saw a rush of mass production, and electrification produced a slew of goods intended (so their manufacturers would have had you believe) to make people’s lives easier. Both Goldberg and Robinson took this obsession with automation of everyday tasks to (and possibly beyond) its logical conclusion. This dependence on new technology, the cartoons said, is ridiculous – just look at us. Novelty does not equal value.

This satirical edge was echoed in the Charlie Chaplin film Modern Times. The ‘Billows Feeding Machine’ is a Rube Goldberg come to life, but also bears a remarkable similarity of conception to Robinson’s pea-delivering machine.

And of course there have been countless examples since, including the Honda advert and many people’s favourites, Wallace’s Cracking Contraptions.

You are, I think, more likely to be able to build a Rube Goldberg than a Heath Robinson – as evidenced by the annual Rube Goldberg machine contest – but I’ve found one delightful example of a real life Heath Robinson. Rob Higg’s wine machine is magnificently impractical, but it does pour an excellent glass of wine, and the satisfaction derived from watching it in action provides its own hit of giddy delight.

My first reaction, on seeing this, was to bark “I want one!” Sadly I’m some years too late (not to mention some thousands light in the wallet department). It was auctioned in 2016, fetching a price of £104,500.

He’s also made this terrific little nutcracker, a handy and welcome addition to any household’s Christmas batterie de cuisine.

Sometimes a Rube Goldberg machine can get insanely busy, and you don’t quite know where to look. The attraction of the linear Goldberg is that you can track it all as it’s happening, although to film one you might need access to a warehouse, as in this anarchic and gleeful video by Chicago band OK Go.

Joseph Herscher, however, gives the lie to the idea that you need space for an enjoyable Rube Goldberg, and his inventiveness and devotion to eccentricity and detail mean that he is now known to many as ‘the Rube Goldberg guy’ (I particularly like the 'melting slab of butter' adaptation.)

But perhaps my favourite is this one, which starts normally enough and then delivers a ‘huh?’ moment about halfway through.

And, as surely as one thing follows another, here is the ‘making of’ film to show you how it was done.

Thing 5 – Penguins

I mean, obviously. All the way back to Volume 4 for this celebration of the mighty pengwang.

A flightless bird is an odd thing. Flying is notoriously difficult, an ability for which most life forms on the planet would kill. And flightless birds just cast it aside like a squeezed out non-recyclable tube of toothpaste.

The reason for this is fairly straightforward: the ability to fly stopped being useful to them. But the trouble is that once you've got rid of it, it's a bugger to get back. And when circumstances change, that can leave you in a sticky situation.

Take the kākāpō.

My heart was won by the description and images of this bird – the world's only flightless parrot, found in just a very few areas of New Zealand – in Douglas Adams’ and Mark Carwardine’s Last Chance To See – the 1989 book and radio series tracking down species on the verge of extinction. (In an interview, Adams rated Last Chance To See as the “personal favourite” of his books.)

Dumpy, nocturnal and elusive, kākāpō are walkers, runners and climbers – that last endeavour helped by some surprisingly nifty beak-work – and their flightlessness wasn’t a problem for millions of years.

Then we came along.

They’d never had to deal with predators before, hence their flightlessness – a common occurrence in island species – so they simply saw no reason to run away from us. The poor fools. Our habit of hunting them and denuding their habitat was only exacerbated by the introduction of stoats and cats and so forth, which need no encouragement to kill a slow and – from the point of view of conservationists – exasperatingly trusting two-kilogram lump of feathered meat.

Flightlessness had served them well for ages – and then, suddenly, it was a disaster.

Another contributing factor to their descent into the ‘critically endangered’ list was their casual attitude to breeding, as described by Adams in this clip:

“It turns out that the mating habits of the kākāpō are incredibly long and drawn out, fantastically complicated, and almost entirely ineffective. People will tell you that the mating call of the male kākāpō actively repels the female.”

Kākāpō are doing better now. Still critically endangered, of course – it’ll be a while before they come off that list – but from a low of around 50 individual birds through the 1990s, they’ve recovered to a population of about 250 – a growth only enabled by concerted conservation efforts.

I would love to meet a kākāpō – a prospect that at the time of writing seems fairly remote – but for now I have to content myself with this clip of Mark Carwardine being shagged by one in the TV series of Last Chance To See (the follow-up Carwardine made with Stephen Fry twenty years after the original book and radio series).

If we find the kākāpō endearing – and we do, we really do – they have stiff competition in that department from penguins. And what with today being Penguin Awareness Day– it seems to come round quicker every year – what better way to mark the occasion than with a brief celebration of the magnificent piebald blubber tubes?

Of the sixty-odd – and they’re all pretty odd, frankly – flightless bird species on the planet, just under a third are penguins. And they are among our favourite birds. Perhaps it’s their posture – upright and dignified, their black-and-white colouring leading to comparisons with footmen or waiters; perhaps it’s that they’re so readily anthropomorphiseable; or perhaps it’s the magnificent sight of them launching themselves out of the water and onto the ice as if fired from a nerf gun.

The extraordinary underwater agility featured in that clip, so at odds with their clumsiness on the ground, owes a lot to their bones – solid, unlike those of most birds – and of course to the way they changed their air-friendly wings into powerful flippers well adapted to propelling them under water.

But playing an equally important role is their plumage. To survive in temperatures as low as minus forty, you need good insulation, and an Emperor penguin’s plumage provides exactly that. The outer layer, made up of short, overlapping contour feathers, is one thing. But underneath is where the magic really happens. Obviously the wodge of fat under the skin helps. But between the skin and the outer layer are two further kinds of feather – plumules and a kind of downy fluff known as “after-feathers” – which provide not just excellent insulation but a further benefit, which comes into its own when the penguins are underwater.

The plumules trap tiny air bubbles, giving the penguins excellent buoyancy, which is denuded when they’ve been under water for a while. So they go back up, have a bit of a preen to restore the buoyancy, dive down again and make their final launch run, leaving that dramatic trail of bubbles in their wake.

Isn’t (and I think I might have said this before) nature (or at least those bits of nature that aren’t us, even though we too have our moments of excellence) wonderful?

When I think of penguins, several things spring to mind. First is usually Werner Herzog’s nihilist penguin.

Next in line is obviously Benedict Cumberbatch and his famous inability to say the word ‘penguin’.

And then of course there’s this classic, fulfilling so many of the basic requirements for a viral internet hit.

Meanwhile, my inner three-year-old (never far from the surface) is always amused by Pingu.

And finally, may I recommend the Penguin Diplomacy episode from Series 2 of the peerless John Finnemore’s Double Acts? Unfortunately these excellent two-handers aren't on BBC Sounds at the moment, but there’s a taster of this episode here:

And if you're going to spend £8 on three hours of delicious entertainment that you will revisit time and time again, then I can think of nothing better. Series 1 is, to my mind, more even in quality (always high in any case), but the high points of Series 2 really are superb, and it’s worth getting for Julia McKenzie’s tour de force in “Mercy Dash” alone.

Thing 6 – Cricket

I still think this one-minute film, from Volume 1, is as perfect a summation of the human condition as you’ll find.

Don’t think of this as a cricket clip. Think of it as a Life clip.

It has everything. Hope, despair, relief, embarrassment, exasperation, self-loathing, fury, and ultimately redemption. It’s the perfect one-minute film, each role played to perfection. Even the wicket-keeper’s Folded Arms of Fury tell their own story.

I wasn’t sure I’d be able to recover emotionally from the nihilist penguin, but a return to Mark Carwardine gettting shagged by a kakapo really helped.

I love Merlin! The migration paths are amazing. Unbelievable, really!