Thing 1: Migration Atlas

The more you learn, the more you realise how little you know.

Take bird migration, with its apparently unending mysteries. How do they do it? Why? When? Where? How far?

You may as well ask the length of a piece of string. Migration is the broadest of churches. Some spend their entire lives on the move; for others it’s just a case of going up or down a hill.

If it’s astonishing feats of aerial endurance you’re after, look no further than the bar-tailed godwit, members of which species seem to delight in breaking each other’s records by small margins on an annual basis, like so many avian Sergei Bubkas. Here’s the latest, a staggering 11-day non-stop journey undertaken by a juvenile bird – named, rather unimaginatively, ‘B6’ – at an average of just over 50 kmh.

That’s 50 kilometres every hour, for just over eleven days, without stopping. It’s exhausting just thinking about it.

As a young birder I learned about the basic rhythms of migration. In the UK this means we get summer visitors from the south (the most obvious and glamorous are probably the swifts, swallows and martins that delight us with their aerial activities through the dog days of July and August), and winter visitors from the north (think straggling arrowhead formations of geese or the thousands upon thousands of waders that perform extreme aerobatic team routines at high tide through the winter over the mudflats of Norfolk).

But those migrations, arresting and romantic as they are – such tiny things, such huge distances – make up just part of the story. Because birds are on the move all the time. And sometimes the identity of the movers is unexpected.

Take the robin. The gardener’s friend, staple of Christmas cards, one of our commonest residents (also, as you might know, possessed of extraordinary aggression towards anyone or anything that dares encroach on what they regard as their territory).

Robins stay put, right? Those same two birds have been coming to the feeder these past six years. We’ve seen them.

Up to a point.

Inconveniently for that narrative, robins have a life expectancy of about two years. So that ‘same robin’ you’ve been feeding all that time will more likely be a succession of them.

But it also turns out that while a good chunk of the robin population does stay put, another chunk is decidedly mobile.

The Migration Atlas, launched earlier this year, brings together over a century of bird ringing records with the latest satellite tracking data to build interactive maps of the movements of over 300 bird species.

It’s quite addictive.

Here’s the map of robin movements – each line is a single bird, ringed or satellite tracked at some point in the last 100 years or so, and then caught again and diligently logged. Safe to say they’re not all just hopping down the road because you get a better class of mealworm at number 68.

You can pick pretty much any bird, and the extent to which populations are on the move at various times of the year makes you blink. Here’s the blackbird, for example. Even the blue tits are at it.

And then you look at the proper long-distance migrants and you have to have a bit of a sit-down. This is what swallows do.

Once you start thinking about it – journeys all over the place, fraught with danger – and start to visualise the reality of it – very small birds, very large distances – it becomes not just astonishing, but deeply moving too, and triggers all sorts of thoughts about the extraordinary fragility and resilience of life.

If bird migration interests you, I can thoroughly recommend Ian Newton’s Bird Migration for an in-depth exploration of the subject. Less exhaustive, but no less fascinating, is Scott Weidensaul’s A World On The Wing.

Thing 2: Literature Clock

The literature clock is a fine endeavour.

“What’s the time?”

So think yourself lucky while you’re awake and remember a happy crew. Think of Hamburg on the Magic Night. 22.50 and they went out neatly, just as they should - you couldn’t fault Parks, he was always on his route.

(The Literature Clock is the work of Johannes Enevoldsen)

Thing 3: Handmade Teapot

Expertise is always interesting. To observe someone doing something difficult – doing it really well, without shouting, swearing, or sobbing those deep heaving sobs that come from deep existential despair in the pit of the soul, but instead going about it with the calmness born of thousands of hours spent acquiring the necessary skills and patience… well, it’s just really satisfying, isn’t it?

And when that process involves smooth surfaces, snug fits, rotating things and the delicious pleasure that comes from watching the trimming of edges until they’re just right, you have something worth savouring.

So here is a slab of clay being transformed into a teapot. Four minutes well spent. And not a heaving sob in sight.

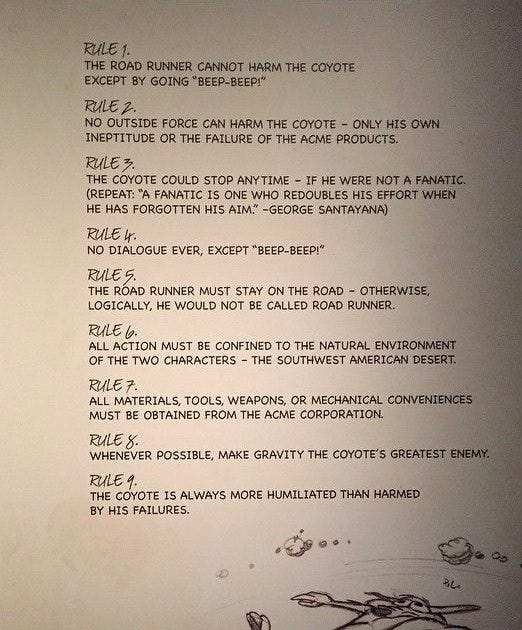

Thing 4: Road Runner Rules

“The road runner cannot harm the coyote except by going ‘BEEP-BEEP’”

Marvellous stuff.

And what do we do to those who tell us that these rules were neither adhered to nor in fact the original work of the makers of the cartoon, but “merely a post-production observation”? We ignore them, that’s what. Spoilsports.

Do you want 20 minutes of the best failed plans of Wile E. Coyote? OF COURSE YOU DO.

Thing 5: A Day in the Life of Wells Cathedral

Photographer Andy Marshall took 1024 photographs of the facade of Wells Cathedral over the course of one sunny winter day. The matrix is fascinating as an indication of how light shifts without our realising it – the transition from coolth to warmth is quite astonishing – and examine it more closely and all sorts of little details emerge.

You can buy the original image as a digital print. There’s also this version with just 100 of the images (in which you can monitor more closely the comings and goings of a car parked just to the left of centre, and also see some of the details of the extremely fine gothic facade).

Thing 6: The Water Game

“When we were young we used to make our own entertainment.”

“Uh huh.”

Thanks for consuming. If you enjoyed it, do tell a friend.

I welcome comments, too. No, really I do.

I remember a few years ago (ok, a quarter of a century ago) driving in the US and seeing a roadrunner run across the road. The disappointment that he was just running, and was not pursued by a coyote, was immense.

It’s a long read but it might be the definitive article on the tragic life of Wile E. Coyote : https://deadspin.com/how-wile-e-coyote-explains-the-world-1752248034