Thing 1 – Cicadas

It’s a big year for cicadas. Huge.

Specifically, it’s a big year for periodical cicadas.

Please sir what’s a periodical cicada?

Glad you asked.

I wrote about periodical cicadas in Music To Eat Cake By. Here’s a bit of it.

Consider, if you will, the cicada.

Specifically, the Pharaoh cicada Magicicada septendecim, found only in the area to the east of the Great Plains of the USA.

They’re quite something. One of 7 species within the Magicicada genus, they’re black with red eyes and a golden gloss to the wing. Rather fetching, to my eyes, although I suspect I’d change my tune were I deposited in a swarm of them, a phenomenon I’d find simultaneously idgy, awe-inspiring and fascinating.

Idgy, because that’s a common reaction to large buzzing swarms; awe-inspiring, because once I’d got over the idginess I’d be entranced by the spectacle; and fascinating because of mathematics.

Magicicada septendecim, like its 6 congeners, has an unusual and specific life cycle. They live, as nymphs, just underground, feeding on tree-root fluids. Then, one spring evening when the soil temperature is just right (above 17.9°C, fact fans) they emerge. All of them. At once.

I’m trying to imagine witnessing this phenomenon. Billions of insects, at a density of a million per acre, rising from the soil and marching doggedly to the tops of trees, there to cast off their nymphoid garb, assume their adult form, mate, lay eggs and die.

They don’t all make it. Many are eaten by predators: turtles, birds, squirrels and such like, all presumably thanking the gods for the surprise presentation of a once-in-a-lifetime all-you-can-eat buffet, even if it is a set menu comprising just one item.

But the predators are soon sated, and many cicadas remain. The survivors breed, the females cutting tiny slits in the bark of twigs, where they deposit the eggs. A couple of months later the eggs hatch, drop to the floor, and burrow into the soil to start the cycle again.

The remarkable thing about this isn’t just that the cicadas have such a long life cycle and emerge all at once, although that in itself is notable – all other cicada species except the Magicicada genus appear annually. No, what’s truly remarkable is the timing. Periodical cicadas (as they’re known) appear either every 13 or 17 years.

Those are odd numbers, aren’t they? Not just ‘odd’ as in ‘odd and even’, but ‘odd’ as in ‘peculiar, strange, abnormal’. And very specific. You’ll already have noticed that they’re both prime numbers, and therein lies the key.

Abundance of prey stimulates predator population size. Stands to reason. A bird with a yen for cicadas would thrive if there were cicadas on tap. From the cicada’s point of view, they want to avoid cicada-eating birds. One way of doing this is by having a long life cycle; another is for that cycle to be a prime number.

Imagine these cicadas emerged every 12 years. On their emergence they could be predated by any animal with a life cycle matching theirs – so anything with a 2-, 3-, 4- or 6-year cycle, those being the factors of 12. By adopting a prime-numbered cycle they reduce that risk.

The cicadas don’t know this, naturally. They just follow their genetic instructions to ensure the continuation of the species.

Cicadas can’t count; evolution can.

So here’s the thing. The reason this is a big year – huge – for periodical cicadas is concisely summarised here on the University of Connecticut’s website, where you can learn everything you ever wanted to know – even if you didn’t realise it – about periodical cicadas. These are the key points:

For the first time since 2015 a 13-year brood will emerge in the same year as a 17-year brood.

For the first time since 1998 adjacent 13-and 17-year broods will emerge in the same year.

For the first time since 1803 Brood XIX and XIII will co-emerge.

You will be able to see all seven named periodical cicada species as adults in the same year, which will not happen again until 2037. You will not see all seven named species emerge in the state of Illinois again until 2041.

Brood XIX, if you’re wondering, is also known as ‘The Great Southern Brood’, and covers a large swathe running from Maryland down to Georgia in the east, and from Iowa to Oklahoma in the Midwest. Brood XIII is known as ‘The Northern Illinois Brood’.

Slightly disappointingly, I read that “13-year Brood XIX and 17-year Brood XIII do not overlap to any significant extent. They may co-occur in patches of woods, but these patches will be small in size.”

If you’re having trouble imagining what this spectacle looks like, Attenborough is, as always, on hand to show us.

Thing 2– Eclipse

If it’s a big year for cicadas, it’s also a big year for the sun and the moon.

The forthcoming solar eclipse on April 8th won’t be visible here in the UK (they very seldom are – the last total eclipse was in August 1999 and the next will be in 2090), but many will understandably be tempted to travel to experience it. If you’re among their number, here’s a guide to help you plan your trip.

A solar eclipse brings to the front of people’s minds a cosmic coincidence which should really freak us out every day, and which is the kind of thing that might just persuade me of the possibility of the existence of a supreme being. It is this: the sun is approximately 400 times further away from earth than the moon, and the moon’s diameter is approximately 400 times smaller than the sun’s. So the two objects look the same size in the sky – if the moon were bigger or smaller or closer or further away, this wouldn’t be the case.

Ridiculous. What are the odds [rhetorical]?

Atlas Obscura has got some fun bits about the eclipse. There’s this, about the first footage of a solar eclipse, filmed by Nevil Maskelyne in 1900

There’s this, about the role of eclipses in literature (disappointingly, though, there’s no mention of Tintin)

And this, with some excellent photographs – not of eclipses, but of eclipse watchers.

If you’re curious about the course taken by eclipses, this should do you nicely: every eclipse ever, tracked.

Thing 3 – Typography

Everything you ever wanted to know about typography terminology in one infographic.

Thing 4 – Dance

This dance, by CDK Company, is strange and wonderful and I love it.

Thing 5 – Blossom

It’s cherry blossom time.

Near me there’s a street devoted to the Yoshino cherries that, for a few days each spring, give spectacular blossom. Up with this kind of thing. I haven’t been able to get across there, but my friend Ben has, and these are his photos. Magnificent. Thanks Ben.

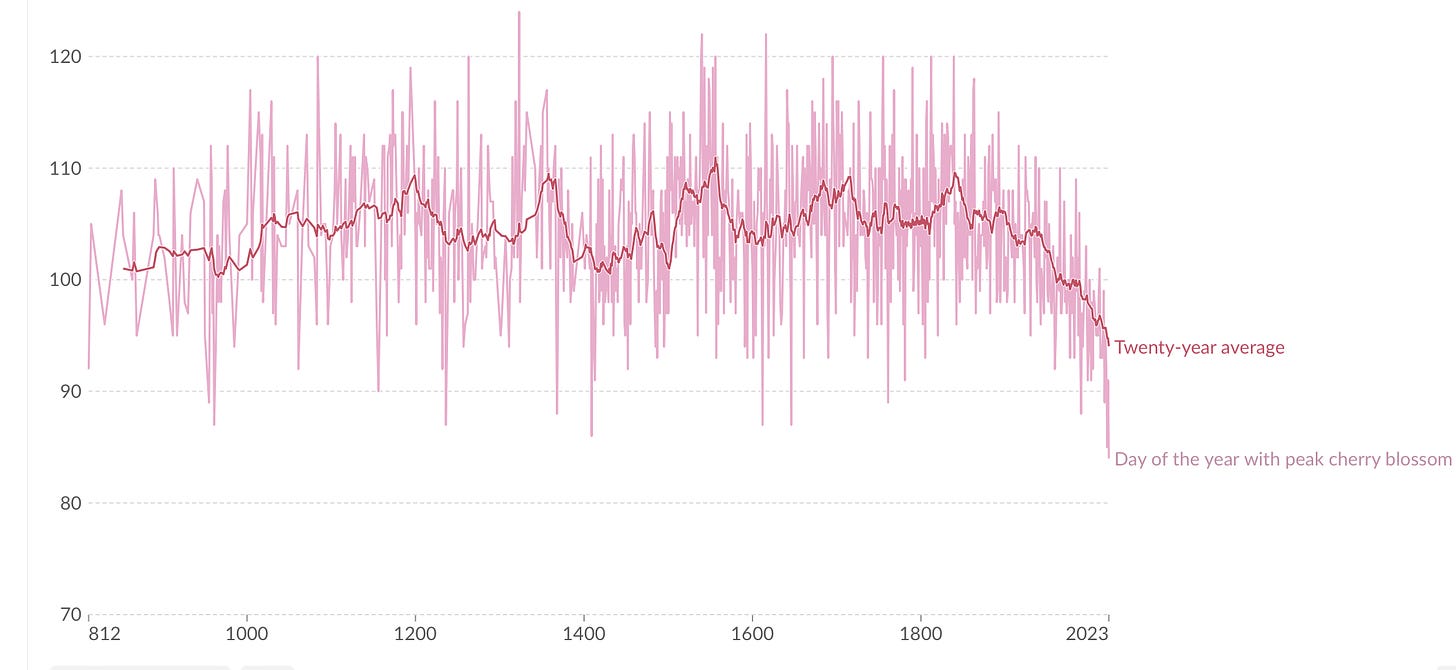

And here’s a fascinating/sobering chart of peak cherry blossom season in Kyoto over the centuries.

Thing 6 – Population

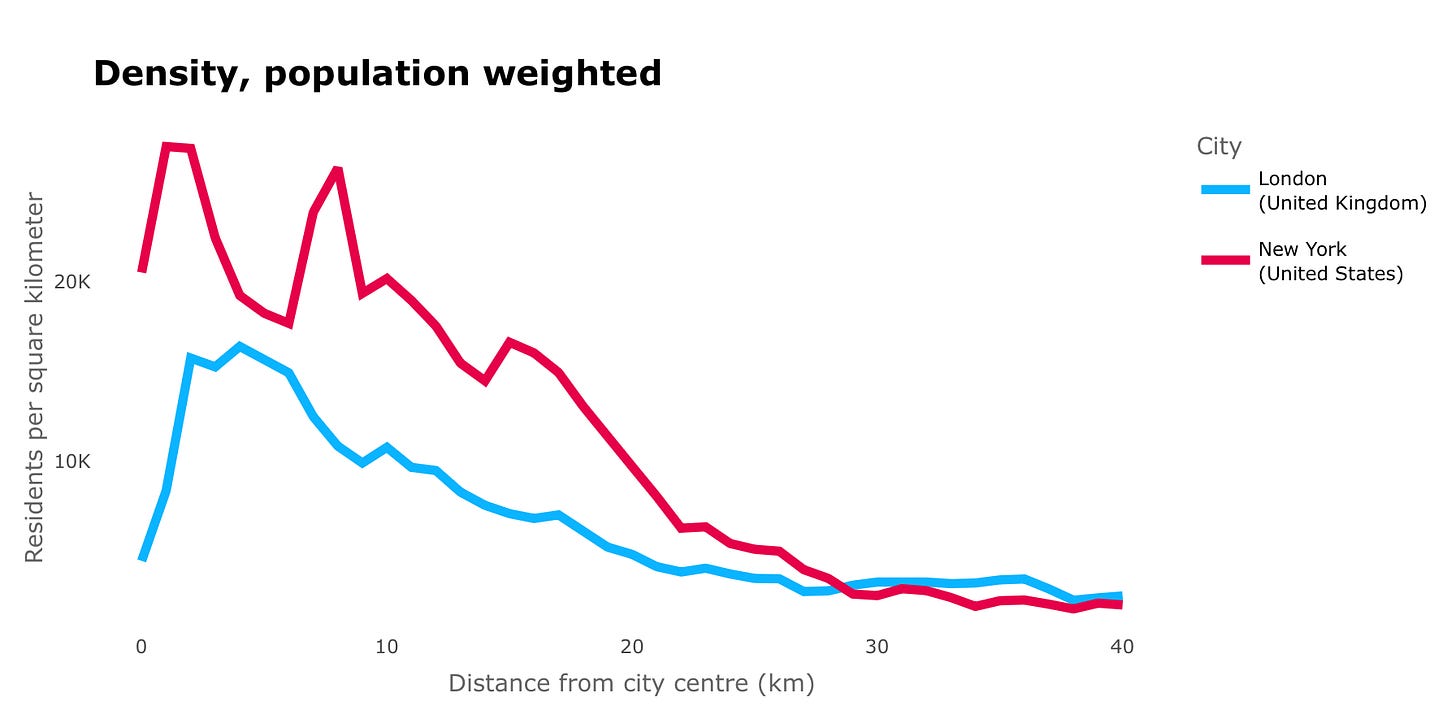

From Jonn Elledge’s excellent Newsletter of (Not Quite) Everything comes this interactive website comparing population densities in cities around the world.

Here, for example, is London vs New York.

There’s plenty of fun to be had choosing ever more unlikely pairings. Helsinki and Delhi, say.

And so the long day wears on. See you next time!

UTTERLY MESMERIZED by that dance video 🤩

I remember the eclipse of 1999 when the clouds got a bit darker. 50% of buisnesses in Cornwall are still called eclipse