Later than expected – apologies. Thank Evernote, which swallowed 1,300 carefully crafted words yesterday morning and has yet to regurgitate them.

Thing 1 – Nests

I’m going to blame Charles M Schulz.

I won’t deny that this is a controversial opening. The great cartoonist was (and still is) rightly revered by many for the as-near-to-perfection-as-makes-no-difference of his art. But he was also responsible for disseminating (albeit unconsciously) one of the Great Lies.

The Peanuts universe, while undeniably good at the big truths of human behaviour, wasn’t entirely rooted in reality. Beagles, in general, don’t sleep on the sharp-edged roofs of their dog houses. Nor do they walk on their hind legs, become world-famous baseball players, or spend hours flying Sopwith Camels, locked in mortal combat with the dastardly Red Baron. And yet all those things became entrenched in the Peanuts canon.

No, this lie was more insidious because of its plausibility. I certainly didn’t question it until many years later. It’s a very small thing, really.

Birds do not sleep in their nests.

That is to say, they do not use their nests as beds, the way we do.

And yet there was Woodstock, time and time again, zzzing away in a familiar-looking twiggy cup.

It’s one of those things that most people rarely think about, and then when someone raises the subject they might go “oh wait hang on though” for a few seconds, shrug their shoulders and give it no further thought as they revert to the main business of the day.

So what are nests for, and if they’re not for sleeping in, where do birds in fact sleep?

Well, it varies. Of course it does. With nearly 11,000 bird species in the world it’s bound to.

The most notorious example of extreme avian sleeping behaviour occurs in swifts and frigatebirds, which can sleep on the wing. As explained in the article, the truth is slightly more complicated than that, but I’m sticking to ‘sleep on the wing’ simply for the ‘wow’ factor.

But this extravagant behaviour – some might call it showing off – is beyond most birds.

Waterfowl, for example, choose a more sedentary position, settling down near water and tucking their beaks under their wings. This is a pose, incidentally, shared by Mei long (‘sleeping dragon’), a 125-million-year-old dinosaur fossil – persuasive behavioural evidence for the link between dinosaurs and birds, if ever you needed it.

Nearly 60% of those 11,000 species belong to the order known as passerines, or ‘perching birds’. They vary in size from really pretty tiny – wrens, say – to actually quite chonky – the raven is the largest.

A couple of anatomical features unite passerines. They share a 3-1 toe configuration – three facing forwards and one facing backwards. This enables the perching behaviour that gives them their collective name. They also (and this is the clever bit) have a tendon (the flexor tendon) in their leg that tightens automatically, allowing them to grip their perch tightly. With the tendon locked, passerines can sleep while perching, without fear of falling off. (This, incidentally, is not dissimilar in effect to an albatross’s shoulder-lock tendon that enables them to hold their wings outstretched for hours on end as they soar over vast expanses of ocean.)

They don’t always sleep while perched. Smaller birds – especially in winter – might find a hole or crevice to hunker down in for warmth and safety. And it’s quite common for these roosts to be communal – the mental image of 63 wrens huddled together is probably the very definition of ‘cuteness overload’ (I wish I could find a photograph of it).

Large communal roosts, whether in trees, reed beds or other places that offer warmth and safety, occur in many species. Starlings are the most obvious example, but I’m particularly fond of the large gatherings of pied wagtails you’ll find in city centres during winter.

As for the nests, they are of course used for incubating eggs and rearing chicks, and come in many forms.

There are plenty of birds that eschew the idea of a nest entirely. For a guillemot, all that’s required is a few square inches of cliff ledge (almost certainly the subject of a future Thing, I’ll just tease you for now with the delightful information that a recently-fledged guillemot is known as a ‘jumpling’).

Also apparently carefree in their nesting habits, plovers and other shorebirds will do little more than make a tiny depression in the ground into which they lay their eggs. There’s a good reason for this. The speckled eggs are camouflaged, often almost to the point of invisibility – defence against predators, but also leaving them vulnerable to destruction by careless humans, whether walkers or, in the case of lapwings nesting on farmland, tractors. Some farmers, aware of this, take the trouble to stake out lapwing nests to increase their chances of survival.

Also ground-based are the many bird species that choose to burrow into the earth. A sensible idea – warmth and safety are built in – and even more sensible if you take over a pre-existing hole. The rabbit or whatever does the hard work, and then you move in afterwards. Burrowing birds include among their number puffins and (pretty obviously, given the name) burrowing owls – this one would like to sod off immediately please thank you.

Continuing with the ‘earth’ theme, pause for a second to admire the skill and perseverance of swallows and martins, patiently building their nests out of mud pellets. It’s not just a question of packing it together willy-nilly, either. The mud needs to be of the right consistency otherwise the nest will fall apart or crack. Extreme dry conditions in spring can make the task of nest-building very difficult. The effort isn’t in vain, though – they will reuse these nests year on year.

The art of muddy nest building is taken to its limit by ovenbirds – again, the provenance of the name is fairly obvious.

The commonest nests, though, are built with vegetation – grasses, twigs and so on. Some are frankly pathetic. Yes, wood pigeons, I’m looking at you.

Building upwards from there in terms of complexity are the many variants on the familiar ‘cup nest’ theme – assemblages of twigs and other materials to make a comfortable temporary home for eggs and chicks. A blackbird’s nest is a perfect example.

When birds get big, the nests unsurprisingly get bigger too. Ospreys take it to extremes (to be clear, the platform was built by humans – birds are amazingly inventive and dextrous, as we’ll see in a minute, but they have their limits).

At the opposite end of the spectrum in terms of size and the dexterity required to build them, we have the miracle that is a long-tailed tit’s nest. Thousands of pieces of moss, spider silk and cocoons, lined with hundreds of feathers and encased with fragments of lichen. All built by both partners over a period of up to three weeks, without swearing or divorce. Beautifully ridiculous and ridiculously beautiful.

But even the efforts of the long-tailed tit pale beside those of weaver birds.

The diligence and skill required to make these intricate, hanging structures is barely believable, and when it comes to the condominium-like structures made by their cousins, the sociable weaver birds, incredulous gawping is very much the order of the day.

Even more amazing to discover that, somewhat counter-intuitively, these complex structures preceded the simpler cup nest, as explained in this film.

Perhaps the most spectacular form of avian construction isn’t strictly a nest. But the shrine-like constructions made by male bowerbirds are probably a story for another time.

Thing 2 – Roads

Any British road-user will be familiar with the road-numbering system. A single letter (M – motorways, A – major, B – minor) followed by a 1-to-4 digit number. The system is just over 100 years old (the first list was published on April 1st 1923).

For most people, that’s enough information, especially if they’ve ever been cornered at a family gathering by an uncle intent on explaining that they were a fool to take the A413 it’s murder on public holidays no much better to stay on the M40 till High Wycombe and take the A4010 through Princes Risborough especially with the roadworks at Wendover.

I don’t want to be that uncle, so I’ll try to keep it brief.

Firstly, one for nostalgia fans: a short film made on the opening of the M1 in 1959. The clothes! The thin moustaches! The giddy excitement on their faces!

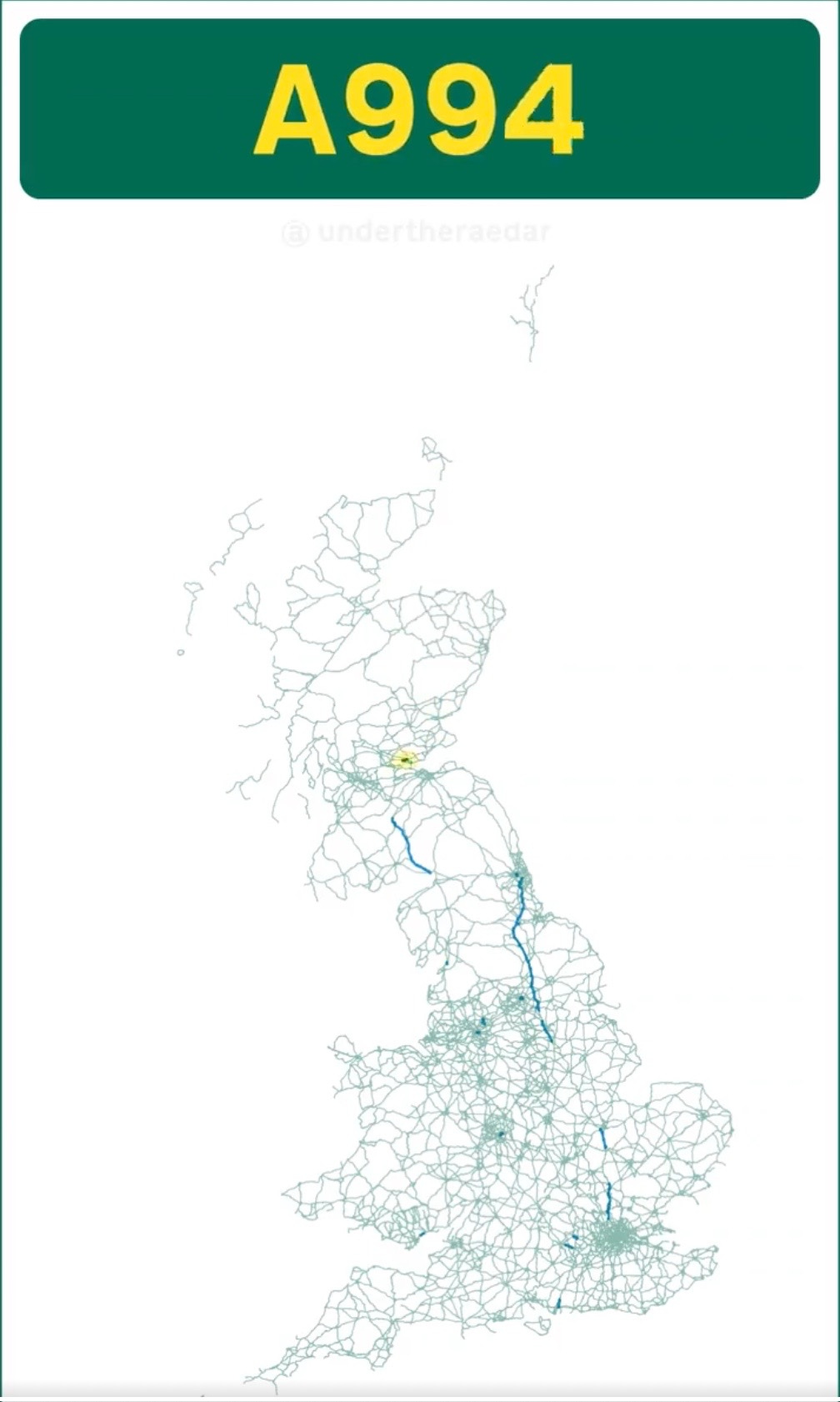

Secondly, and the thing that triggered this, it’s worth watching this really rather alluring visualisation by Alastair Rae of all the A and M roads in Britain, from A1 to M90. I especially like the way the shape of the British isles emerges as the film progresses.

Thing 3 – Code breaking

Atlas Obscura has a good collection of puzzley-type things. My eye was, not unnaturally given my heritage, drawn to this code-breaking conundrum (as a non-Armenian-speaking half-Armenian – long story – I didn’t find it quite as straightforward as you might expect.)

Thing 4 – Protecting birds

Many people have a protective instinct towards birds, and this is only to be welcomed. Sadly, though these instincts sometimes have the opposite of the intended effect.

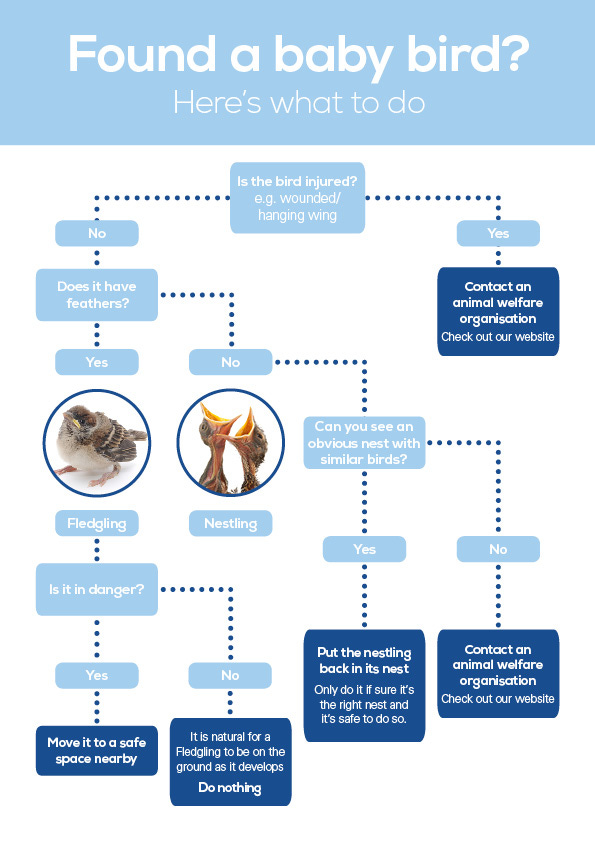

As it’s the season for it, here’s some advice on what to do if you find a baby bird.

And it turns out that window films work better if you put them on the outside.

Thing 5 – Forfar/East Fife

It was a running joke for any football fan growing up in the 1970s. Any meeting between the two Scottish teams Forfar and East Fife was eagerly anticipated in the hope that the result would be East Fife 4 Forfar 5, or any one of numerous variants.

We had to make our own entertainment back then, you see.

One of the variants – Forfar 5 East Fife 4 – happened in 1964. And then in 2018 the dream score finally came to pass – except that the full time score was 1-1 and the 5-4 only applied to the penalty shoot-out. Which, as far as I’m concerned, doesn’t count.

So imagine the delight, at season's end, when Scottish League Two finished like this.

I think we can finally lay it to rest.

(Sidebar: is there anywhere, in any sport, a more delightful sports team name than ‘Bonnyrigg Rose’? If you know of one, do tell.)

Thing 6 – Pollinators

This, by James Sutter, made me cackle.

You can see the original tweet and its replies here, and follow him here.

Pigeons are hilarious when building nests. It's amazing the species survives, let alone in the numbers it does!

Loved reading this. I won't lie to you, I thought birds used their nests like beds until today.

The swallows and the swifts have arrived in the place where I live - some of my favourite birds. I would love to find out about the neuroscience of how swifts sleep while flying.