Thing 1 – Archaeopteryx

What is a bird?

There are nearly eleven thousand of the things, from hummingbird to ostrich. What is their unifying characteristic?

Nowadays, this is a fairly straightforward question. The bird, like grief or hope (depending on your choice of author), is the thing with feathers. Even the kiwi’s hairy poncho is made up of feathers, even though it doesn’t immediately seem like it.

Birds have other features – they’re toothless, generally have extremely light bones, and of course, whether they use them for flying or not, they have wings (in the case of the above-featured kiwis the wings have shrunk so much that they’re effectively invisible under that poncho). But these aren’t uniquely distinguishing characteristics. Feathers are. Birds – and only birds – have feathers.

It wasn’t always so clear cut.

When I was a child, it was – or seemed – so simple. The first bird was Archaeopteryx lithographica. It lived 150 million years ago, and the first fossil was discovered by Herrmann von Meyer in 1861.

Here’s one, the so-called ‘Berlin’ specimen (there are a dozen Archaeopteryx specimens, several of them preserved in extraordinary detail, and each one shedding light on an existence in many ways entirely alien to ours, but still carrying enormous weight and resonance and capable of giving me a bit of a frisson when I stop for a few seconds to ponder the general ooh-ness of whatever).

What a thing. What a fabulous, bizarre, other-worldly thing, reaching across vast unimaginable tracts of time to remind us (should we be listening, which we usually aren’t) of our true place in the grand scheme of things.

So entrenched was Archaeopteryx in its position of avian primacy that its German name was (and still is) ‘Urvogel’ – ‘first bird’. The second and third birds, whatever they were, were consigned to the dustbin of history.

But things change, informed by new discoveries. And since my childhood – when that information was imprinted on my brain, thanks to the now defunct Pears Cyclopaedia (I think – memory is fickle) – the state of play in the world of bird fossils has developed significantly.

This altered state of affairs owes a lot to the many fossil discoveries made in the Laoning area of China in the 1990s. Things like Sinosauropteryx prima (‘first Chinese lizard wing’), a feathery thing with a very long tail and short arms discovered in 1996. Or the pheasant-sized Microraptor, which liked feathers so much it grew them on all four limbs. Or Xiaotingia zhengi, dating from about five to ten million years earlier than Archaeopteryx, making it (depending on who you talk to) either a much better candidate for the title ‘first bird’ or not a bird at all, just something bearing a resemblance to what we now recognise as birds.

There were plenty more – creatures, that, while superficially strangely familiar to a modern nature enthusiast, would differ from our modern birds in various ways: bony tails, teeth, more feathers, fewer feathers – many variations on the theme. If Archaeopteryx were to be discovered today, it would be merely one of a host of feathery winged dinosaurs from around that time, lots of them looking, acting, and possibly – for all we know – sounding like the birds that are so familiar to us today.

If it looks like a bird, fossilises like a bird, and makes an as-yet-unspecificed-sound-that-we-might-be-able-to-conjecture-about-but-can’t-really-be-certain-what-it-was like a bird… well, it must be a feathery dinosaur. But where that dividing line comes – between unequivocal dinosaur and unequivocal bird – is, to a great extent, dependent on your own personal definition of the word ‘bird’. And the progression was messy, with many strands.

As for flight, it was in its infancy; for this brand of vertebrates, at least (pterosaurs had been doing it for aaaaages, but that’s another story). Some did it passably, others just barely, while yet others had mastered the art of gliding to a greater or lesser extent without yet making the transition to powered flight. Archaeopteryx itself was probably, at best, a weak flyer.

And the definitive answer to how it all started – trees-down, ground-up or a possible mixture of the two – remains unanswered, although the suggestion mooted by Ken Dial of ‘wing-assisted incline running’ has attractions for proponents of both the alternatives (and certainly gets my vote, for what little that’s worth).

What is a bird? It’s the thing with feathers.

Perhaps.

I’ve written a great deal more about this particular bit of the history of animal aviation in the ‘Archaeopteryx’ chapter of Taking Flight, the publication of which is now less than three weeks away. Ulp.

Thing 2 – Grouse

You are, let us say, a male Black Grouse (‘blackcock’, if you prefer the older, more informal name. Lyrurus tetrix, for the scientifically inclined). There are many worse things to be. Black grouse are strange and alluring birds, and one particular aspect of your behaviour is rightly regarded as one of the wonders of the natural world.

It’s April, and the urge is upon you, as it so often is at this time of year. It’s lekking1 time.

Here’s what you do.

Get yourself to an open grassy area at dawn, along with a dozen or so of your fellow males. You, as one of the dominant males, take a central position. The others, the subordinates and juveniles – they can watch and learn.

Your tail feathers, white against deep black, play an important role. So do the bright red wattles above your eyes. By such things will the females (known as ‘greyhens’) assess your worthiness.

You fan your tail. You flare your wattles. You make a bizarre bubbling sound, as if humming along to a mid-90s techno track.

You run at your rival, jump, flap your wings, bump chests. Repeat. Show them what’s what, who’s who, and just where they’re going wrong in life. The females – you just know it – are bound to be impressed. Because that’s why you’re doing it. Territory and mating – explanations for so much behaviour in the natural world (and that includes us, obviously).

Here’s a clip from a black grouse lek, taken and posted by Mary Colwell (whose books are recommended, by the way). I particularly like the attitude adopted by both birds as they exit, with the implied ‘yeah, OK then, but I could have had you ANY TIME’. (Click on the photo to watch.)

Thing 3 – Nightingale

A short film about the most poeticised of British birds. It’s not in any way undermined by the recent admission that the famous nightingale/cello duet was a hoax.

Thing 4 – 1,729

OK. Enough birds. Let’s have some numbers.

I’ve always loved the story of the Ramanujan number – proof, if it was ever needed, that you can find interest in anything if you look and think hard enough.

Or can you?

Perhaps there are interesting numbers and boring numbers. (Requires a free account, but it’s worth doing, I’d say).

I was delighted to discover, via the article above, the existence of The Online Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences. You’ll find the prime numbers there. And the Fibonacci sequence. And my favourite, the Lazy Caterer’s Sequence. And many many more.

It turns out that 20,067, by dint of appearing nowhere in the Online Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences, is potentially the most boring number. Which, of course, makes it doubly interesting.

Thing 5 – Colour

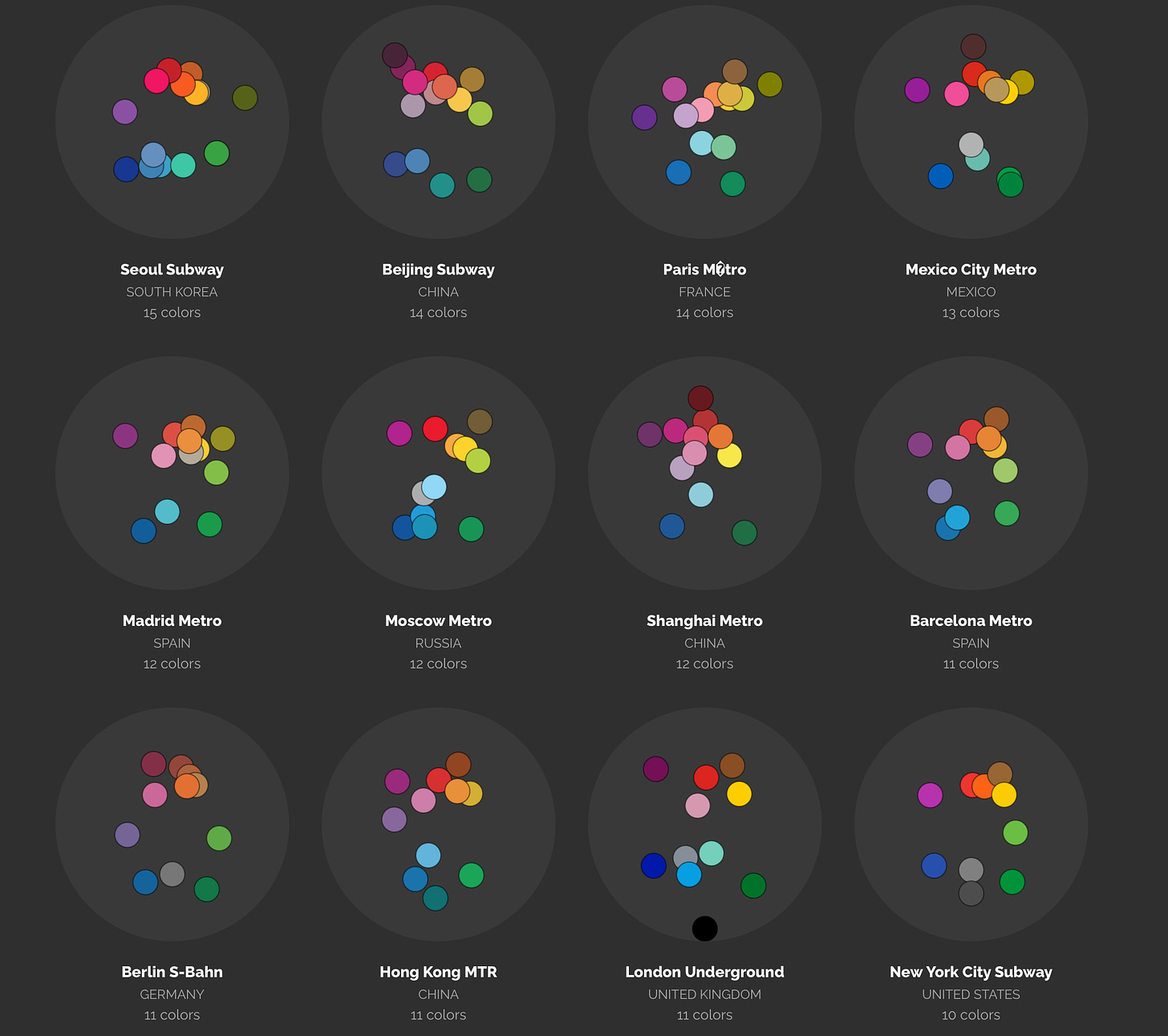

The Global Subway Spectrum is a marvellous thing based on a simple concept. All they did was log all the colours used on all the subway maps in the world, and chart them in different ways, thereby opening up a world of joy.

It’s the kind of idea you have when doing the washing up or on a walk or doing something else that allows the mind to wander and produce strangely creative things. And then to bring it to life… well, it’s the ultimate rejoinder for anyone who ever utters the dismal phrase “someone’s got too much time on their hands”. What is time for, if not to produce things like The Global Subway Spectrum?

I have mostly contented myself with scrolling through it and murmuring ‘ooh, pretty’. Luckily for all of us, Jonn Elledge has done a slightly more rigorous analysis. Do subscribe to Jonn’s newsletter, by the way – always interesting.

(In case you were wondering, the only two occurrences of black are on the maps for London and Bilbao.)

Thing 6 – Leaves

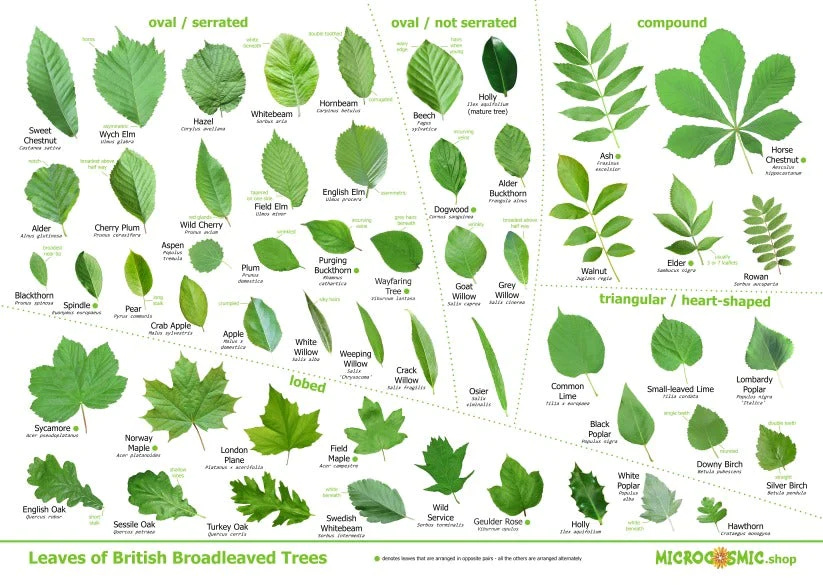

This one is of most use to UK people, although no doubt there is some crossover for other places, depending on where you live.

It’s merely a handy chart of tree leaves, either to help you identify them in the coming months, or just as something pretty to look at.

It’s the work of Phil Barnett (@squinancywort1 on Twitter). He has a website where you can download this and other things (including similar charts of bark and buds), or buy a print. The posters are free, but you can also make a donation if you like. He gives 10% of profits to the World Land Trust. So, you know, good things.

‘Lek’ comes, so I learn, from an Old Norse word meaning ‘play’.

Lovely stuff, Lev. And I bought two mugs. Blue tit and goldfinch.

Evolution of flight vid was fantastic. Made total sense. 😊