Hello! This is the first of the mid-weekly posts sent to all those on the Birds list. If birds aren’t your thing, you can unsubscribe from these posts by going to the manage your subscription page. But do have a read anyway – you might find that birds are, after all, your thing.

For this first volume, I’m making the whole thing available to everyone, just so you can have a taste of what you might be in for if you take out a paid subscription. The first piece each week will always be available to everyone, but in future weeks everything below that will be available only to paid subscribers. Whichever category you fall into, your support is very much appreciated.

The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Robin

A frosty, dusky walk. Bright, low sun makes a world of glare and shadow and angles. Muddy paths acquire a thin icy glaze. Spillikins treetops reach for the sky. Christmas trees line the streets, forlorn and abandoned.

Peak January. The usual deal.

Later, there will be hot chocolate and some sort of comforting bun. But not yet. There’s still time to wring a bit of life out of the short – but gradually lengthening, oh yes – hours of daylight.

Cutting through the low rumble of South Circular traffic, a familiar sound. A piping, trembling warble, a silvery ribbon with judiciously placed gaps. Here is a bird that knows and understands the importance of silence.

Sing. Wait. Sing. Wait.

A robin, doing what robins do. A year-round singer, leading the way, showing the others how to do it. They’ll join in, soon enough.

Tswee-ooOoOo-s’b’widdle-ibalooOOoo. Tsib-a-lib-a-tsweeee.

I register the sound with a distant part of my brain. Register it, forget it, move on.

And then I remember the Fundamental Principle By Which I Live (Or At Least Try To Live).

The FPBWIL(OALTTL) is this.

There are nearly 11,000 bird species in the world, and every single one of them is rare or unknown somewhere. So when you see a common, familiar bird, treat it as if this is your one and only chance to see it.

It’s all too easy to forget this FP. All too easy to see a blue tit on the feeder and think ‘blue tit, yeah, whatever’, when the instinctive reaction should be ‘FUCK ME just look at that thing look at its colours look at its perky gait OH MY GOD IT’S HANGING UPSIDE DOWN JUST LOOK.’

It’s possible to take the FP too far, of course, walking around in a state of slack-jawed wonder at the very existence of a blade of grass, like a coke-fuelled Fotherington-Tomas (‘hello clouds, hello sky, hello blade of grass like WOW AMAZING I did not know blades of grass did that HAVE YOU EVER SEEN THAT I’ve never seen that’). But it might, just might, nudge you towards a state of alertness, a willingness to look at the familiar in a new light.

Whenever I need a reminder of the FPBWIL(OALTTL) I think of the Beijing robin.

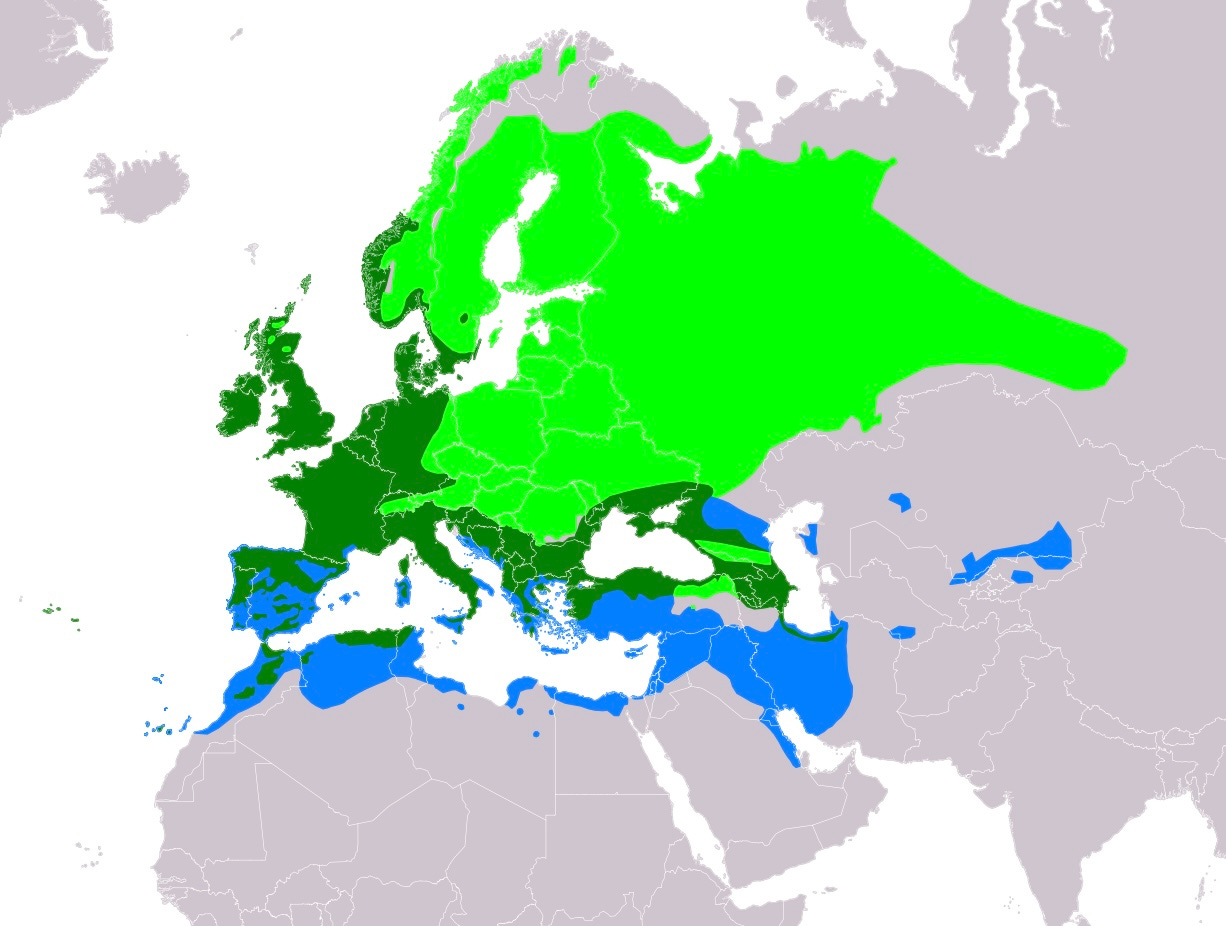

The robin – or, I should clarify for international readers, European Robin Erithacus rubecula (as opposed to any of the 100 or so other birds that contain the word ‘robin’ as part of their name) – is ubiquitous across its regular range. As a result it’s often taken for granted. This applies especially in Britain, where it is known as ‘the gardener’s friend’ for its pleasing habit of hopping up and perching on fork handles because it knows that forks mean worms and it couldn’t actually give a shit about humans except as a source of free food just to say hello out of the goodness of its little avian heart.

But that range is, in the grand scheme of things, not large.

So if a European Robin turns up somewhere else it understandably causes a bit of a kerfuffle. In this case, ‘somewhere else’ was Beijing.

The Beijing robin is at the heart of the FPBWIL.

And so it is that on hearing this piping, warbling, trembling song, this silvery ribbon of sound with its judiciously placed gaps bespeaking a bird that knows and understands the importance of silence, I stop and I look and I listen.

It takes a few seconds to find it. That’s often the way. Natural ventriloquists, robins. So often, they’re lower and closer than you think. And so it proves. It’s at eye level, about five yards away. Close enough for me to meet its gaze. I like to think the extra squiggle it gives the next phrase (twee-oo-sibilib-a-tsweeeee-tswi-tswi-spleeeooo) is for my benefit.

The egotism of humans. It’s not trying to impress me, this robin. That’s just a happy coincidence. Birds sing for two reasons, we’re commonly told. To attract a mate or to defend a territory.

But perhaps they have other motivations. Perhaps this one is doing no more than making sounds it finds pleasing. Perhaps it’s just announcing its presence to the universe, saying ‘I am here – make of me what you will’. Perhaps, along with every other life form on the planet, it’s just doing its best to get through the day, and when that’s done it allows itself a little sing. And perhaps that’s a routine we might all do well to adopt.

This is the point at which, in future weeks, I’ll insert a paywall. Sorry about that. I hope that the above kind of thing will be enough for you, but gluttons for punishment might want more.

War and Peace and No Birds

I’m reading War and Peace.

Big book, War and Peace. You may have heard. 1300 pages in the Maude & Maude translation. 361 chapters. The work – if you’re doing it the way I am, as part of Simon Haisell’s ‘chapter a day’ read-along – of a year.

There are quite a few people taking part in this read-along, and many of them are sharing thoughts and ideas in the comments and weekly chats. I’ve mostly steered clear of these, not because I don’t have thoughts or ideas, but simply because I don’t feel I have much to add to what is one of the most studied and discussed books ever written. Also, this is my first time reading it and I’m just enjoying the ride (and a most worthwhile ride it’s proving to be).

But one thing occurred to me as we reached the fortnight mark. Something fundamental that I suspect has never been remarked on before.

There are no birds in War and Peace.

This is, on the face of it, hardly surprising. There are, after all, 580 human characters to contend with, and Lev Tolstoy has enough on his plate making sure he’s keeping the reader up to speed with them all (I call him Lev partly because it gives me a sense of kinship, and partly because a person being known by more than one name is absolutely in keeping with the spirit of the book).

War and Peace’s avian dearth is probably for the best, because I have no doubt that Lev Nikolayevich, had he ever bothered to turn his hand to it, would have been an excellent and prolific taker of field notes. Here he is on page one, describing Prince Vasili: ‘He had just entered, wearing an embroidered court uniform, knee-breeches and shoes, and had stars on his breast and a serene expression on his flat face.’ This is the kind of economy of description encountered in field guides: ‘olive-brown upper parts, with orange-red bib, short and thin bill, and slim body that can appear rotund when feathers are puffed up.’ A bird-filled War and Peace might well have run to 2000 pages or more.

The book’s extensive human cast list is one of the reasons cited by people who have shied clear of tackling the book. That, and the war bits. I haven’t reached the war bits yet, so I’m not qualified to comment. But a cast list of 580 (so far I’ve encountered a paltry 49 of them) will be familiar to anyone who, considering the noble hobby of birdwatching, has started riffling through a field guide. The War and Peace newbie has to contend with a surging sea of Russian names, patronymics and diminutives, apparently specifically designed to confuse, daunt and exasperate (especially if you make the mistake of reading the list at the beginning of the book before you start). The discovery that Count Nikolai Ilyich Rostov is also at various points referred to as Nicolas, Nikolenka, Nikolushka, Kolya or Koko might be enough to induce the faint of heart to throw either in the towel or the book across the room (always assuming you have the strength – seek the advice of a medical practitioner before embarking on any physical exercise programme).

And so it is with birds. Dipping into the ‘warblers’ section of your Collins guide you find, in close order, a sequence of small brown birds: reed warbler, sedge warbler, marsh warbler, grasshopper warbler, Pallas’s grasshopper warbler, and a few dozen others to boot. Daunting enough even when they’re lined up nicely in the pages of a book – which isn’t, you’ll be dismayed but not surprised to learn, how birds tend to present themselves in the wild – but next door to impossible in the field until you’ve gained a fair bit of experience. And given the enormity of the task, why would you bother? The situation is only exacerbated by birders’ habit of giving birds nicknames – ‘gropper’ and ‘PG Tips’ being the sobriquets for the last two on that list.

So many birds. Where do you start?

Well, you could simply start with the bird in front of you. That’s the approach I’m adopting with War and Peace. Who is this person? What do they look like? Are they related to someone else I’ve already met? Will I remember them? DOES IT MATTER?

That’s the crucial one. Does it matter that you can’t remember who the hell Princess Elena Vasilievna Kuragina is, whether she’s the same as Hélène, Elén or Lyólya (yes, yes and yes), or what her relationship is to Prince Vasili (daughter). Probably not. Live in the moment and enjoy immersing yourself in Tolstoy’s world – it is a superbly rich and varied one. (I speak purely on the basis of the first 17 chapters – I might change my tune once we start getting into the weeds with detailed descriptions of military manoeuvres.)

And with birds the situation is remarkably similar. Knowing the difference between a host of sandpiper species is a hell of a challenge, as per this, the funniest and most accurate tweet of 2023:

But that’s not your way in. Your way in might easily be something like this.

Who cares what the birds are called when they can do that?

Start with the bird in front of you and take it from there. You won’t go far wrong.

Big Garden Birdwatch

If you’re in the UK you might want to start with your bird-in-front-of-you-ing by signing up for the Big Garden Birdwatch. It’s the annual citizen science bird survey run by the RSPB, and it’s taking place over the weekend 26th-28th January. All you do is count the birds that visit your garden in a single hour of the weekend. There’s a good guide to it here, and here’s the RSPB’s own video explainer.

Based on years of experience, the usual routine goes something like this:

8.55: fill feeders, get binoculars, notepad, pencil, coffee.

9.00: wait, prepared for whirlwind of bird counting

9.00 - 9.58: no birds

9.58: a solitary blue tit, perched just outside the official counting zone delineated by your garden fence, considers a foray to the feeders

9.59: it decides not

10.01: birds – thousands of ‘em! – emerge from their hiding places, faces wreathed with smiles

Despite this, I do urge you to consider taking part.

Albatrosses and Infrasound

Fascinating new research on Wandering Albatrosses suggests they might – might – listen to infrasound to help them find their way around the vast, featureless (to us) oceans.

Every time we learn something new about birds, it seems only to underline how little we know.

Shaw Bird

“My language was fairly moderate considering the number and nature of the improvements on Mozart volunteered by Signor Caruso”

Finally, here’s a marvellous letter by George Bernard Shaw detailing his suboptimal experience at the opera. Essential reading for anyone who has ever had their view obscured by a massive head – it could always be worse.

Omg the analogy between Tolstoy’s characters and a bird guide is brilliant

‘Indeed, the irony of its appearance in the current political climate has not been lost on Chinese media, who are dubbing the bird a "Brexit refugee".’ 🙂