Magpie

“Hello Mr Magpie, how’s your lady wife?”

Then spit three times.

My mother told me to do that when I saw a lone magpie, to ward off bad luck. I don’t suppose she believed it for a second. It was just a habit, a slice of folklore from whenever, repeated just because.

Besides, you never know. What if you forgot, and then the next day your head fell off in a freak breakfasting accident? What then?

Best greet the magpie, just in case.

You might have a version of it. In fact, if you grew up in Britain and are of a certain age, I’m pretty sure you will. Some salute them with an “aye aye Cap’n”; others with “hello blackie”; still others might hold on to their collar until they see a four-legged animal to counteract the malevolent potential of this most recognisable of British birds.

The black-and-white colouring that gives it the second part of its name (the first syllable is a contraction of ‘Margaret’) conceals rather more subtlety than first meets the eye. Catch it in the right light, and you’ll see an entirely pleasing iridescence on the wings and tail – green to blue to purple, shifting and glinting. And I hope I’m not alone in admiring the geometry of its splay-winged, long-tailed form in flight, the tail feathers sometimes slightly fanned.

I know there are many who don’t share my fondness. This can happen if you’re a bird with a taste for raiding the nests of other birds and feasting on their chicks. While the emotional response is entirely understandable, and in a way a heartening reflection of the devotion we feel towards our garden birds, the level of vitriol directed towards magpies (which are, after all, merely taking advantage of a nutritious and seasonally abundant food source) also offers insight into the human tendency to divide nature into ‘good’ and ‘bad’. And when we see something as ‘bad’, we won’t hear a word said in its favour. That the increased abundance of magpies in the last few decades has coincided with a decline in songbird populations only fuels the outrage.

Inconveniently for this narrative, though, a 15-year study by Tim Birkhead and his team found that the increased in magpies had “no detectable effect on songbird breeding success or populations in rural habitats”. We hate to admit it, but one way and another, the main reason for declining bird populations would seem, most often, to be us. Awkward.

While a lone magpie is a portent of unnamed, non-specific misfortune, the rules change as the groups get larger. As the familiar rhyme has it:

One for sorrow

Two for joy

Three for a girl

Four for a boy

Five for silver

Six for gold

Seven for a secret never to be told

If you grew up in Britain in the 1970s, the version that formed part of the signature tune to the children’s programme Magpie might be the one you know, continuing like this:

Eight for a wish

Nine for a kiss

Ten is a bird that you must not miss

The curious reader might wonder what happens if you see more than ten magpies? How about eleven? Twelve? Thirty?

You’re in luck. Step forward the comedy god – and occasional reader of these words HELLO JOHN – John Finnemore, who, in the last episode of Series 9 of his Souvenir Programme, took the magpie rhyme to – and, frankly, well beyond – its logical conclusion.

As a sidebar, the whole series is a work – and at this point, John, if you are indeed reading this, you might want to look away to avoid quite blatant ego-inflating toadying – of unparalleled genius.

Anyway. You can find said rhyme at 9’20” here – it has to be said that as this is the last episode of a six-episode series, the whole of which is made up of what seem at first to be individual sketches but turn out to be interconnected in wonderful but admittedly complex ways, you’re probably better off listening to the whole series from the beginning if you want to make any sense of the episode, but if all you’re after is the rhyme, then head to 9’20” as previously described and feast your ears. For those lacking the gumption, discipline and moral fibre to click a link and slide a slider, here’s the poem in all its glory.

One for sorrow

Two for joy

Three for a girl

Four for a boy

Five for silver

Six for gold

Seven for a secret never to be told

Eight for a wish

Nine for a kiss

Ten for a chance you must not miss

Eleven for a wasp

Twelve for a bee

Thirteen for a coffee

Fourteen for tea

Fifteen for a pencil

Sixteen for a pen

Seventeen to hear these options once again

Eighteen for pepper

Nineteen for salt

Twenty for an accident in which you were not at fault

Twenty-one for Jerry

Twenty-two for Tom

Twenty-three - where are all these magpies coming from?

Twenty-five no seriously

Thirty this is weird

Forty-eight from where have all these magpies suddenly appeared?

Sixty-two stop counting

Seventy just run

Ninety-nine the revolution of the magipies has begun

Two hundred no more sorrow

Five hundred no more fears

One thousand for how long the empire of the magpies will last in years

Shelduck

Feathers are quite the thing. Strong and lightweight, they protect, insulate and decorate. They also, by way of a sideline, enable flight. Decent work, feathers. Take the rest of the day off.

There’s just one snag. They wear out and need replacing on a regular basis.

Faced with this inevitability, you can take a variety of approaches.

You can moult gradually, replacing them bit by bit. Many birds do this, and even within this basic strategy there’s a wealth of variation.

Ducks are different. Ducks – many of them, at least – take a more gung-ho view of things.

“Let’s crack on through,” they think. “Replace all our flight feathers at once, in one short burst. That way we might be flightless for a bit, but soon enough we’ll look as good as new and be ready for the rigours of the new season. And hey, what’s the worst that could happen?”

“You mean apart from being a literal sitting duck for a predator?”

“Look, I think we’ve all had enough of this negative talk, don’t you? Whatever happened to the never-say-die attitude that made duckdom great?”

Flightlessness, however temporary, does indeed make a bird more vulnerable to predation. And with feathers taking their sweet time about growing, a couple of months of sitting-duckery can be disastrous. Shelducks, among others, have developed a solution to counter this danger. They simply fly somewhere else after breeding and complete their moult there. The somewhere else needs to be a safe place, where resources are abundant and the risk of predation low.

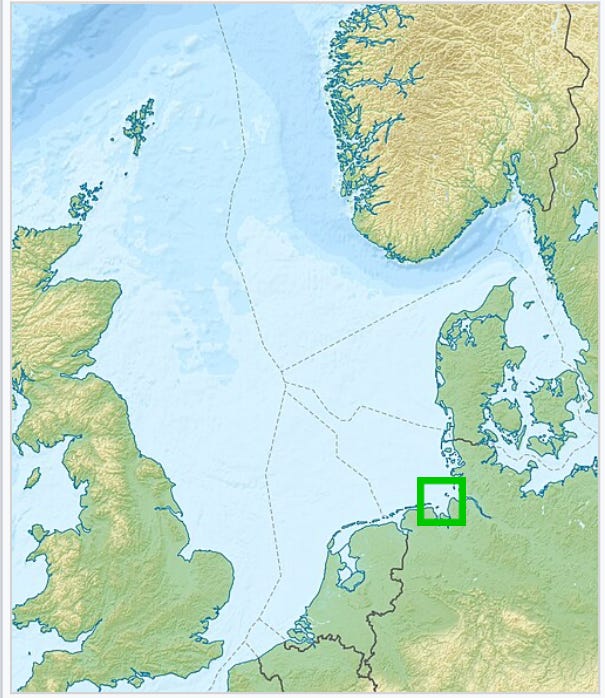

Just such a place is the Heligoland Bight, off the German coast – a large intertidal zone where they can feast on their favourite mud snails and be fairly certain they won’t be eaten by land predators, which tend to be picky about the squelchiness of their hunting grounds. The Heligoland Bight is so well suited to their specific needs that shelduck from all over Europe – up to a quarter million of them – head there in midsummer so they can moult in relatively stress-free conditions.

And while they do that, a small number of non-breeding adults stay behind and look after the young – not yet ready to travel – in what’s unsurprisingly known as a ‘crèche’. These crèches form while the chicks are still young, and are sometimes made up of a hundred or more birds, all under the care of a handful of adults – hard work for the grownups, no doubt, but an effective and welcome example of individuals within a species cooperating for the greater good, rather than going to great lengths to beat off the competition.

Also, and not for nothing, a shelduckling crèche is an endearing sight.

Did you know that magpies can't fly upside-down? You probably kind of assumed it, without any specific information to the contrary. Ah, but does the *magpie* know this? Well, maybe it's worth a shot, if there's some food available...

So I'm watching this magpie on the roof of the bungalow opposite. There's clearly some tasty titbit under the rather long overhang of the eaves. How to get it? Hmm... stand in the gutter and lean over? Nope, too far away, I keep falling off the roof. How about leaping up from ground level? I'm not a great leaper, but with wing-assistance, maybe? It's only a bungalow, so it should be... nope, that doesn't work either. Okay then, swoop in from the side and flip over at the last minute, picking it off as I fly past in a majestic barrel roll? Ow, ow, ow. *Very* bad idea.

There is also this amazing version of the magpie song by the Unthanks, which featured in the final series of Detectorists

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=w6EIFD80f90&ab_channel=BBC