Word 1: plinth

It started as a joke, a silly throwaway tweet.

Funny word, plinth. It popped into my head because I was looking at one. It had a sphinx on it, as they sometimes do, especially if they are the ones at the top of Crystal Palace Park in south London, near where I live.

The curious might ask why I chose ‘plinth’ when ‘sphinx’ was right there. They might have a point. But it’s no use questioning history.

From “‘plinth’ is a good word” to “what are some other good words?” was the work of an instant, and from there to a Twitter poll pitting four words against each other the work of a few seconds, the delay merely the result of my getting my phone out of my pocket.

Such is the way of the extremely online.

The ‘1/1024’ bit was an afterthought, as if mocking myself for the naffness of the idea. There's an element of that, I think. A deflection.

“I'm doing this, but I wouldn't want you to think for a moment that I'm taking it seriously.”

There was never any intention to see it through. After all, only a lunatic would post 1,024 word polls.

Hello. It's me. I'm the lunatic.

I don’t know who posted the first ‘World Cup of...’ Easy to think it was Richard Osman, whose name springs to (UK) minds when the format is mentioned. Maybe it was. In any case, they've been part of the fabric of Twitter since polls were first introduced in 2015. World Cup of Crisps. World Cup of Chocolate. World Cup of British Symphonies. World Cup of Trinkets on My Aunty Vi’s Mantelpiece.

I did a World Cup of Tintin Books once. The final was a tie between Destination Moon and The Blue Lotus. As my friend Nathan drily remarked, “That was a worthwhile exercise.”

Part of me was convinced that a good portion of my followers would, as it became clear that I was committed to the bit, either roll their eyes or just leave. Maybe they did.

And yet I persevered.

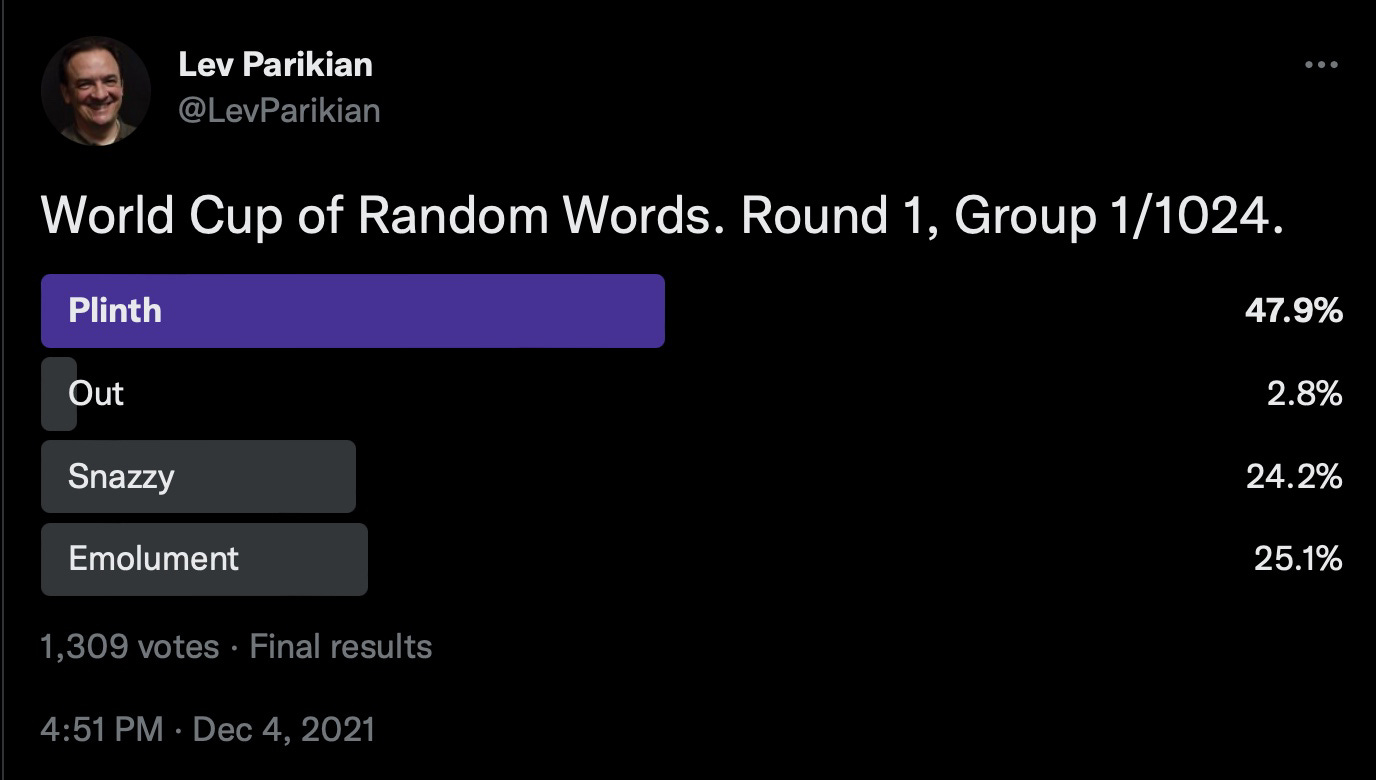

‘Plinth’, as I’d hoped, won that first group, making short work of ‘out’, ‘snazzy’ and ‘emolument’. Group 2 followed fairly quickly, ‘frond’ despatching ‘pioneer’, ‘that’ and ‘abstain’. In the third, ‘gusset’ was too strong for ‘good’, ‘cushion’ and ‘mandible’, though this group in particular sparked vigorous debate, ‘gusset’ being one of those words – like ‘moist’ – arousing strong emotions.

And so the long month wore on.

Soon, as I worked my way up to 20 groups, then 30, then 40, it became clear to everyone, not least myself, that this was going to run and run.

I started a spreadsheet. I couldn’t run the risk of a word, inadvertently repeated, meeting itself in the final.

For a moment I entertained the notion that ‘plinth’, the very first of the 4,096 words in the competition, might also be the last one standing – an outcome that would have been both anticlimactic and extremely funny.

But it was not to be. It met its match in ‘gusset’ in Round 2. Farewell, ‘plinth’ – you have no idea what you started.

Word 2: that

Not much of a word, you might say. Ordinary. Nondescript. Frankly dull.

And that was rather the point. From the beginning I was keen not to forget the little people. The flashy words, the likes of haberdashery, smithereens, vicissitude, hullabaloo and such like, they would always feature. But language is built on the ordinary, the words holding it all together. ‘Other’, ‘forty’, ‘often’, ‘perhaps’, ‘of’, ‘because’, ‘red’, ‘under’.

And then there were the everyday words of another kind, the sort your English teacher tells you to eschew (‘eschew’ is just the kind of word your English teacher would approve of – it reached Round 5, where it was knocked out by ‘pugnacious’). ‘Say’, ‘do’, ‘be’, ‘have’, ‘good’, ‘bad’, ‘happy’, ‘sad’.

‘Love’.

They were all knocked out in Round 1, those words. I knew they would be. But it’s not the winning, it’s the taking part. Or so we’re told. And, to my surprise and pleasure, people did take part. Enough of them to make me feel the whole enterprise wasn’t entirely worthless.

Enablers, the lot of them. If you’re hanging around with a spare finger of blame, looking for a target, look no further than those loyal voters.

Twitter being Twitter, it wasn’t long before the objections started. It was pointed out by my friend Outi, a true internationalist, that calling this a “World” cup wasn't exactly respectful to... well, literally every country except England.

So the World Cup of Random English Words became the “World” Cup of Random English Words.

Then someone, spotting the suspiciously curated feel of some of the rounds, asked me whether the words were in fact randomly chosen.

Say hello to the “World” Cup of “Random” English Words.

I had no reply to the person who asked if there would in fact be a trophy for the winning word at the end of it all (if indeed we would ever reach that point, which at the time of asking seemed unlikely.)

OK then. “World” “Cup” of “Random” English Words.

It felt only a matter of time before someone challenged the authenticity of ‘words’ and possibly even ‘of’. Thankfully they made it through unscathed.

But as for “English”…

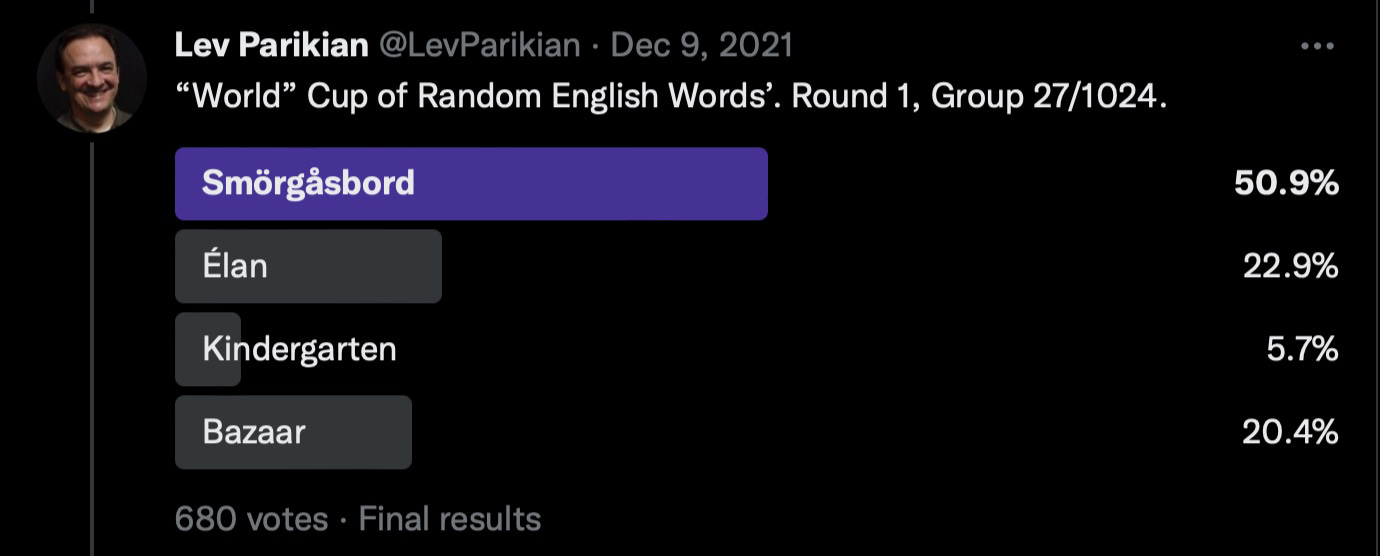

Word 3: smorgasbord

The longest-running complaint (and, I’m afraid, the most irksome) first surfaced in Group 26, with the appearance of the word ‘dungarees’.

“That’s not an English word!”

Well, duh.

My response was swift and – so I thought – conclusive.

I hadn’t reckoned with the adhesiveness of Twitter. For linguistic aficionados this turned into a bonanza, while for me it became a bête noir. My gung-ho attitude – I admit I occasionally allowed loanwords to run amok – was, in the eyes of some, gauche, de trop and even grotesque. But I kept my mojo and esprit de corps, manned the stockades, and withstood the onslaught (even though it sometimes drove me doolally). I went to great lengths to prove that such words are kosher, if only to stop people from kvetching. Only then could I prove to the hordes that, while a renegade, I’m a savvy mensch, not a putz.

The point is, English (as demonstrated by the heavy-handed paragraph above) nicks words from other languages. And it doesn’t mug them in a dark alley. It walks up to them in broad daylight and says “I say, old chap, I’ll just take this if you don’t mind, ta ever so.”

The chutzpah of it.

Claire Copperman put it more generously.

Anyway, of the many loanwords in this whole farrago, I think my favourite might be ‘smorgasbord’ (or, if sticking with the original Swedish, ‘smörgåsbord’). I note, in passing, that smorgasbords are always – ALWAYS – ‘veritable’.

Word 4: discombobulate

I carefully avoided making too many personal statements throughout the seemingly endless thirteen months of the World Cup of Random English Words (WCOREW for short, a really clunky acronym – I didn’t think it through). You don’t want the referee taking sides, after all.

But now I can say it.

‘Discombobulate’ is not a good word.

gasps

There are plenty who disagree, of course. That's how it got to the quarter-finals, beating ‘diaphanous’, ‘rambunctious’, ‘lake’, ‘faff’, ‘squirrel’, ‘hootenanny’, ‘ruminate’, ‘rigmarole’, ‘hedgehog’, ‘nincompoop’ and ‘rhubarb’, before succumbing to the mighty ‘bollocks’.

It feels like a good word for a while. All those lovely syllables. The ‘bob’ in the middle, enabling you to do your best Blackadder impersonation. And the vague impression it gives that the speaker is in some way a word person. Ooh that’s a long word. Very impressive.

Uh huh.

The same goes for ‘flibbertigibbet’ and ‘higgledy-piggledy’. Lovely and shiny on the shelf, played with for a week, but soon discarded. Fun words, but not proper words.

Here’s an idea. The next time you’re tempted to say ‘discombobulated’ try saying ‘disconcerted’ instead. Or ‘disturbed’. Or, at a push, and in the right circumstances (and particularly if you give it a bit of the Werner Herzog) ‘deranged’. You’ll find your life immeasurably improved, and you’ll never look back, I promise.

Other opinions are, as always, available.

Word 5: bollocks

If the World Cup of Random English Words could be said to have a ‘people's champion’, it was ‘bollocks’. A bit of a contradiction, of course, as the words that proceeded through the competition were the winners of popular votes, so by definition the ‘people's champion’ is also the actual champion, but that’s just nitpicking.

Of all the words that fell by the wayside, none did so to louder, more anguished howls of despair than ‘bollocks’. Its appeal is obvious. It’s not too rude (‘fuck’ went out in the first round, victim of a prudish electorate), and it is, by any objective analysis, extremely enjoyable to say. But for all its many fans, it had detractors, too. They shook their heads sadly at the prospect of a bollocks victory. The actual state of things, I don’t know, the barbarians are at the gate, the ravens are preparing to leave the tower, what is the world coming to?

By this time, it had all got rather out of hand. A feature by the estimable Patrick Kidd in The Times Diary in the run up to Christmas led to further media coverage, and the enticing prospect of Radio Four’s Today programme having to announce the winner without saying the word ‘bollocks’.

There was also a faint worry that the influx of new voters would undermine all the hard work done by the 700 or so loyalists who’d been with it from the beginning. But in truth, the increase in voter numbers merely reinforced existing voting patterns. And despite strong support from a handful of celebrity voters, and the hint of an astonishing comeback in the semi-final, the bollocks fairytale came to an end.

Word 6: shenanigans

It’s easy for me to say this now, but I had ‘shenanigans’ pegged as the winner a long way out. There’s something about it that has broad appeal. It lacks the tweeness of the flibbertigibbets and higgledy-piggledys; it’s not rude like ‘bollocks’ or ‘wanker’ or ‘fuck’ (in an alternative universe these two fight out the final, and Radio 4 explodes); it has a hint of espièglerie (“that’s not an English word!”)

It’s often misused, I think. As here, in a tweet announcing a series of – hold on to your hats – Zoom calls.

And for my own personal taste, that’s its downfall – that hint of forced jollity, always offputting.

But its frequent misuse isn’t really the word’s fault. I wouldn’t have chosen it myself (I can come off the fence here as a massive ‘bollocks’ fan), but its victory wasn’t a fluke. On another day, it might have succumbed to ‘murmuration’ in Round 4, but that and the semi-final aside, it thrashed all-comers to sweep to a resounding victory.

All hail shenanigans. Meanwhile, all the other words go into training for the next edition, learning lessons and coming back stronger.

Afterword

So now it’s all over, what are the overriding memories? The final rounds attracted a fair amount of attention, and the palpable division into camps rooting for individual words will stick in the mind. Little did I suspect, just fifteen months ago, that my most quoted tweet of 2022 would be appended with the battle cry “COME ON BOLLOCKS”.

Most of all I’ve been surprised and delighted that so many people became so invested in it. When asked about it, I’ve been keen to emphasise just how ludicrous it all is. And I really do think it’s ludicrous. Its very premise is fatally flawed. Words are communication tools. Deciding whether one is ‘better’ than another is like deciding whether Mozart is ‘better’ than Rembrandt. (Do feel free to insert your own analogies here – I realise mine is not the strongest.) It felt both fascinating and somehow wrong. That’s not words are for.

But perhaps it is, after all, what they’re for. In part, at least. Several people claimed – I think they were being serious – a new appreciation of words as a result of this apparently absurd exercise. Who am I to argue?

In some ways, the first round was the most enjoyable. Taking a couple of minutes, four times a day, to choose the words became a soothing routine. I tried to make the words in each group bump against each other a little bit, to give the collection a sort of rhythm.

Groups of death popped up, almost by accident. ‘Wanker’, a really strong word, came up against the faintly obscure glamour of ‘palimpsest’. ‘Footwell’ – one of the great Alan Partridge words – might have appealed to a minority, and would have won many another group, but never stood a chance against such powerful opposition. ‘Ear’ was the also-ran.

At times, I found myself in opposition to the choice of the people. “But… but… that’s a terrible word”, I would mutter to myself with dismay.

And there were disappointments, too. I privately mourned the defeat of ‘apothecary’ in Round 2. A few groups later, the superb ‘athwart’ bit the dust. ‘Bap’, ‘posset’, ‘quadruped’, ‘futtock’, ‘finagle’, ‘sprauncy’ and ‘kittiwake’ – all defeated by shinier opposition, either boasting easy onomatopoeia or the cheap allure of the polysyllable (I blame Susie Dent, but don’t tell anyone I said so).

At the end of it all, perhaps the best that can be said of it is that it gave some people a bit of harmless fun. And if that really is the case, then it was indeed – thanks, Nathan – a worthwhile exercise.

Inevitably, I produced merch. You can buy T-shirts, hoodies and more for all of the semi-finalists (bollocks, shenanigans, codswallop, higgledy-piggledy) as well as for this rather fetching word cloud of the top 1000 competitors.

All the results, from plinth to shenanigans, are here. Click on a word to find out how it did, and – thanks to the peerless Jon Pinnock – find out its etymology and so forth too.

And super-WCOREW-nerds can download the master spreadsheet here, enabling analysis of all kinds imaginable (and some unimaginable).

Thanks for consuming. If you enjoyed it, do tell a friend.

I welcome comments, too. No, really.

Claire Copperman nails it (as so often!)

Thanks, from one of those whose word-appreciation was enhanced by this thing!

If “The Mighty Bollocks” were not a ska-punk band in the early 80s, then that was the vital failure that led, inexorably, to Brexit, Trump, and the rise of the Elon Muskovites.