Thing 1 – the music of Burt Bacharach

Thing 1 was going to be something else, but that can wait.

Twitter lit up with tributes yesterday in a way I haven’t seen since the death of Stephen Sondheim. And as with Sondheim, the songs just kept on coming. After about thirty, I realised I hadn’t seen the same song twice.

For far too long I failed to appreciate Burt Bacharach’s music. I forget why. It was probably too ‘easy listening’ for my young tastes.

More fool me.

But even if you weren’t a fan, his music was always there. Look down the very long list of his song titles (and especially the ones he wrote with long-time collaborator Hal David) and you’ll find yourself nodding. “Oh, that one… oh yes, and that… oh did he write that?”

I like connections (they were at the heart of the Thing 1 that got shunted by Bacharach’s death). And with Burt Bacharach you can make just about any connection you like. The list of collaborations his career encompassed is of course extraordinary – from Marlene Dietrich to Dr Dre and plenty of stops in between. I’m currently listening to the album he made with Elvis Costello in the late 1990s, and yes. Yes please.

From the classical musician’s point of view it’s the names of his teachers that jump out: Darius Milhaud, Bohuslav Martinů, Nadia Boulanger, Henry Cowell.

It was Milhaud who gave Bacharach one of his most memorable lessons. The young composer had written a sonatina for violin, oboe and piano (I’d be fascinated to hear it). As Bacharach told the story:

“You know, it was very extreme music that people were writing — we were all influenced by 12-tone music, Alban Berg. I had this one piece at the end of the semester that I got to play for Milhaud — not with violin, not with the oboe; I had to just do it at the piano. I was very, very reluctant when it came to the second movement, because it was quite melodic instead of being harsh and dissonant and avant-garde.”

Milhaud – himself a prolific composer whose music incorporated a wide range of idioms – sensed this and told him:

“Never be ashamed of something that’s melodic, that one could whistle.”

I suppose it’s just about possible that Henry Cowell offered similar advice, but somehow unlikely. Cowell was an avant-garde composer whose experimentation with pianistic techniques first manifested itself in a piece called Dynamic Motion (written in 1916), which he later described as "a musical impression of the New York subway". The sounds produced by slamming the keys with fists, palms or even the whole forearm are a central part of Cowell’s music. Critics of the effect would liken it to the kind of thing a child might do when given a piano and no adult supervision whatsoever. Have a listen and pound the keyboard if you agree.

Further experimentation led to effects more easy on the ear, such as this strikingly beautiful, short piece of music – Aeolian Harp – using sounds from inside the piano (if you only listen to one of the two Cowell pieces, I suggest you make it this one).

(Incidentally, what with this and the George Crumb last week I seem to have got stuck in a loop of giving you bizarre American piano music to listen to. It’s just one of those things that happens, and isn’t a deliberate attempt to alienate my readership – reams of Bacharach will be along in a minute, I promise.)

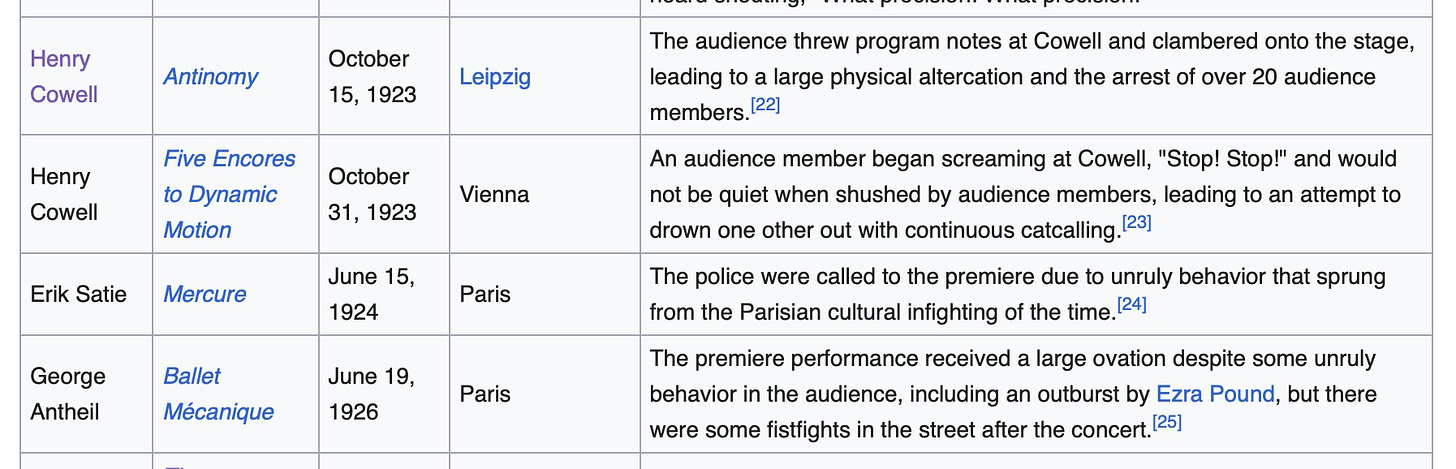

Cowell’s career as a leader of the avant-garde was, not entirely surprisingly, dogged with controversy. Notably, in 1923, he gave two concerts in Leipzig and Vienna, both of which appear on this marvellous list of “classical music concerts with an unruly audience response”.

It would be a stretch to pretend that you can explicitly hear Cowell’s influence in Bacharach’s music, but as he said in the interview below, “It certainly helped to be aware of the extreme extent of some of the music I was exposed to … there’s a stockpile of musical knowledge that you assimilate. I was never much for the plain vanilla three-chord song.”

You can say that again.

Writing a catchy tune that people can sing is one thing; writing sophisticated songs with unexpected harmonies, shifting time signatures and constantly inventive melodies is quite another. And to do both at once – and then repeat the feat year on year for decades – feels like a kind of alchemy.

Here’s a playlist of Bacharach songs – one a year, from 1957 to 1972. You could make a dozen similar lists.

Here he is rehearsing I Say A Little Prayer with Dionne Warwick.

Here’s a short interview about songwriting from 1964 with Magnus Magnusson.

For those who want more detail, here’s a fascinating 50-minute interview about the composition process.

And finally, this isn’t the best version of Close To You, but it is the funniest.

Thing 2 – the music of John Williams

OK, look, if we’re doing great nonogenarian composers, let’s also celebrate John Williams’s 91st birthday. Harrison Ford might disagree, mind.

Thing 3 – petrels

It started in the first lockdown. Things To Distract Yourself With.

You can watch just about anywhere on a webcam. But for all the romantic allure of the Grand Canal, the peace of a beach in the Maldives, or the hubbub of 42nd Street, it was perhaps unsurprising that my instincts led me towards offerings of an avian nature. And soon I found the site of my dreams. Here I found myself spying on the lives of ospreys, hawks and albatrosses.

And hummingbirds. I mean, obviously.

I’d open them up, look in every so often, and forget about them, until wrenched from a reverie by a surprising squawk or chirrup from the corner of the room, the source of which was a terrifying mystery until I remembered the extent of my tab-opening habit.

The exact nature of the allure is elusive. Very little happens. And perhaps that’s it – the very uneventfulness of the experience is reassuring. Just birds, getting on with their lives, completely oblivious to external disruptions.

Their unfamiliarity to me was another attraction – it was an opportunity to familiarise myself with non-British birds – and the feeder-cams would occasionally host a brouhaha, ruckus or fracas to raise excitement levels a notch (starlings and tufted titmice don’t always get on, and don’t get me started on blue jays, the pesky scamps).

The Bermuda petrel cam proved particularly fascinating. There they were, sitting in a burrow in the middle of the Atlantic (3,434.82 miles away from my front doorstep, according to Google maps), doing – mostly – nothing. And I couldn’t, for reasons that aren’t entirely clear to me even now, tear my eyes away. Tiny, distant lives, right there on my screen.

Perhaps it’s the romance of their story. Bermuda petrels – or ‘cahows’, as they are known locally – are an example of a ‘Lazarus species’. We spent 300 or so years thinking they were extinct. And then, in 1951, a very few turned up – seven nesting pairs. A toehold. They were there all along, of course – we just weren’t looking properly.

Conservation efforts, thanks largely to the work of Bermudian ornithologist David Wingate, have ensured a steadyish growth in their population, but they remain extremely vulnerable, particularly to overwashing of the burrows caused by hurricane surges. Back in the 1950s the threats were mostly predation, nesting competition from other birds, and the damage done by the pesticide DDT (which caused egg-thinning, leading to a far higher breeding failure rate).

There’s always something.

I’ve met petrels. Not the cahows of Nonsuch Island, but the storm petrels of Skokholm, off the coast of Pembrokeshire. When I first held a storm petrel chick in my hands, two things struck me.

The first was a thought:

“Why the blithering fuck haven’t I done this before?”

The second was their smell – slightly smoky, musty, as if the bird had just been taken out of long-term storage in a box that also contains some decaying charcoal. While strong, it is – to me, at least – an entirely pleasant smell, both reminiscent of other scents and at the same time entirely unique. If I close my eyes and concentrate hard I can con myself into summoning it – or something like it – into my nostrils. We are not good smellers, humans, and memory is unreliable, but that one sticks, as does the sound of their calls – described by naturalist Charles Oldham as “like a fairy being sick”.

By contrast, here’s the sound of two Bermuda petrels, reunited at the nesting burrow at the beginning of the breeding season.

Soft, intimate, moving.

Bermuda petrels are now off the ‘critically endangered’ list and are merely ‘endangered’. But with a population of just 134 nesting pairs, optimism remains cautious.

By checking in on them occasionally – albeit from a distance of 3,434.82 miles – I like to think I’m doing my bit.

Thing 4 – quintessential bowls

You don’t need to be a bowls fan (I’m not particularly, but could be susceptible to its slow, unhurried rhythms) to be tickled by the perfection of this.

Thing 5

“We’re goin’ on a road trip.”

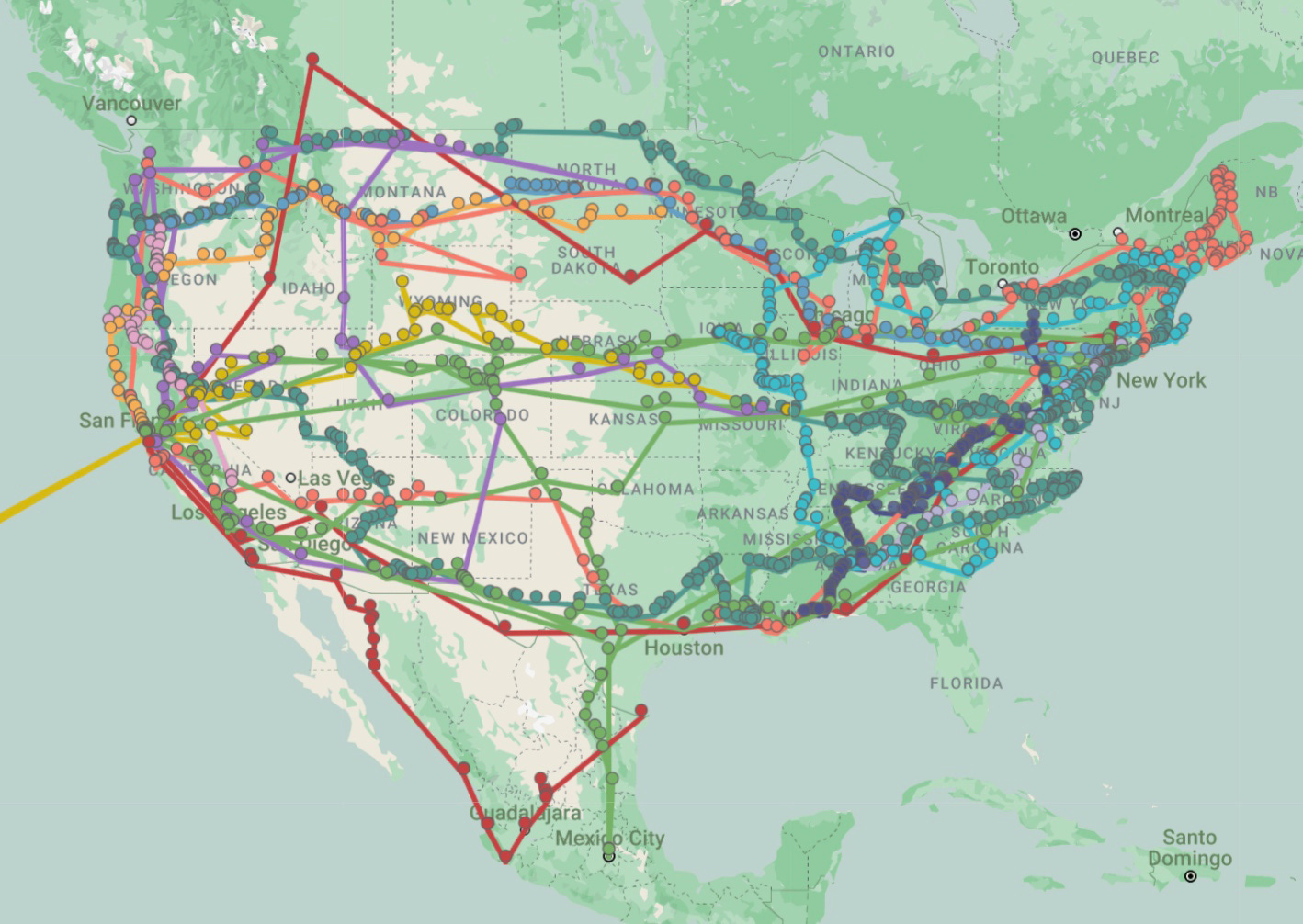

“Shall we just stay at home, make ourselves a nice cup of cocoa, and look at a detailed map of great road trips in literature instead?”

“Yes. Yes, let’s do that.”

Thing 6 – sloths

Of course.

Think I’ll just spend the rest of the day watching the slothanage video on repeat ...

Oh my. Sloths. A pack of fine green beans can never now be seen without thinking of them.