Thing 1 – Hummingbirds

You write a book. You get it as right as you possibly can. And then you pray that nobody publishes anything in the immediate aftermath that debunks or overturns or even mildly but politely disagrees with something you wrote in it.

So far, six months after publication, I think I’m in the clear. But a recent discovery did at least have me thinking of ways I could shoehorn it into the paperback edition.

It concerns hummingbirds.

Nobody of sound mind needs persuading of the marvellousness of hummingbirds. Speed, agility, colour, size – all seemingly designed by a master hand to elicit admiring coos from humans.

Had you ever sat down to think about it, you might have wondered how they manoeuvre around their cluttered environment. To get to that flower with the tasty nectar, it’s almost inevitable that you’ll have to squidge yourself through tiny gaps, and you don’t want your wings – flapping at anything up to 80 times a second, depending on species – catching on a leaf or a branch, the hummingbird equivalent of snagging your sleeve on a door handle. Most tiresome.

So you evolve strategies for getting through gaps smaller than yourself.

Gap Strategy No. 1 – Bullet

Hummingbirds have uniquely constructed shoulder joints – a ball-and-socket affair with a rotation arc of up to 140 degrees. This enables them to flap their wings in a flat figure-of-eight and produce lift on both the upstroke and downstroke.

But while they excel in the shoulder department, their wrists and elbows joints are comparatively deficient – unlike other birds, they can’t fold them. But what they can do is pin their wings in to their body – all they then need to do, when confronted with a small gap, is generate enough speed to get through it without plummeting to the ground, pin their wings and aim. Speed is one of many areas where hummingbirds excel, and if the gap is relatively short as well as narrow, this isn’t too much of a challenge.

If you’re the kind of person who accelerates towards lane-narrowing bollards, you would use the bullet strategy. For the more cautious, there’s:

Gap Strategy No. 2 – Sideways

In this approach, the bird keeps flapping, but angles their body so they pass through the gap sideways. A bit like getting a sofa through a doorway, but quicker and smaller and more feathery and also, now I think of it, not that much like getting a sofa through a doorway but good enough for now. I’m tired.

Whichever strategy is chosen, the speed and timing of the manoeuvre has to be precise. And precision is another area of hummingbird excellence.

It all adds up to yet another reason to bestow all the admiration at our disposal on these remarkable birds.

This is where I read about it. And here’s the original paper.

While we’re on the subject of hummingbirds flying through things, here’s an older (but no less fascinating) piece describing what can and can’t fly through a waterfall. And if you prefer visual explanations, it’s summed up in this short film.

Eager for more on hummingbirds? OF COURSE YOU ARE.

Here’s the marvellous Katherine Rundell. (Her book, The Golden Mole, is now so firmly on my ‘to read’ list that no amount of scrubbing or detergent will ever remove it. Somebody please buy it for me for Christmas.)

My only tiny gripe about this piece by Maria Popova is that it’s no longer thought that feathers evolved from scales. Current thinking is that they went instead from simplicity (a simple hollow tube) to complexity (for example the advanced flight feather as found on the wings of all flying birds). There’s more here, for those so inclined.

Thing 2 – Ghost Signs

The world is full of things you (or, in this case, I) were sort of dimly aware of but had never thought about that much. Take ghost signs – old hand-painted adverts that, either through care or indifference, have been preserved in at least a version of their original state. I’d seen them about the place but never realised they had a name or that people would, say, maintain blogs devoted to them or write books about them.

Enter Sam Roberts, who catalogues and researches them on his excellent site Ghost Signs – a proper rabbit hole of history, beautifully researched and full of gems.

Naturally, what I did first was look for ghost signs local to me. Pleasingly, there are several, including Waygoods and Bryant & May (pictured above).

Of particular interest to Londoners will be Sam’s book, Ghost Signs: A London Story. And there’s a map of them, including suggested ghost sign walks.

Thing 3 – Bird wall

Oh, I like this.

Of course I do.

The Cornell Lab of Ornithology does excellent birdy things, including the extremely popular Merlin app, webcams, the indispensable Birds of the World, and online courses for all levels.

Now there’s the Wall of Birds, a mural at their visitor centre in Ithaca, NY.

It’s almost as if they painted it for me and me alone.

For those who can’t get there, they’ve made an interactive version. I’ve just spent a happy half hour delving into it, exploring birds I know and birds I don’t, learning about them and occasionally voting for them (at the time of writing the most popular is the Southern Cassowary, closely followed by the Blue-footed Booby).

This three-year project, occupying 280 square meters, features representatives of all 243 bird families in the world, with a bonus section charting their evolutionary history. It’s the work of Jane Kim, to whom all kudos.

If the wall of birds inspires you to attempt an emulation in your kitchen, she has prepared this PDF with step-by-step advice for painting birds. And there’s a webinar (I use the word only because they use it – if I had my way it would be banished to the darkest regions) with Jane painting an American Avocet (cracking bird) here.

Thing 4 – Maps

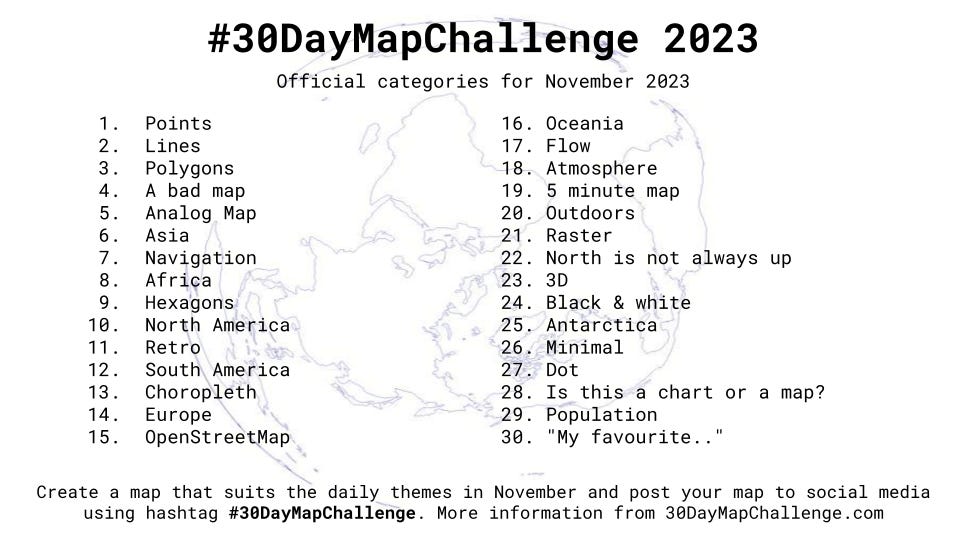

This month sees the annual iteration of the 30-Day Map Challenge, one of the last bastions of excellentness on the Platform Formerly Known As Twitter.

Every day has a different prompt. It’s open to everyone. If I had the first idea how to make a map on my computer I’m sure I’d participate. But I don’t, so I merely enjoy the work of those who do. Some of them are excellent, some odd, some just plain daft.

Here are some of my favourites.

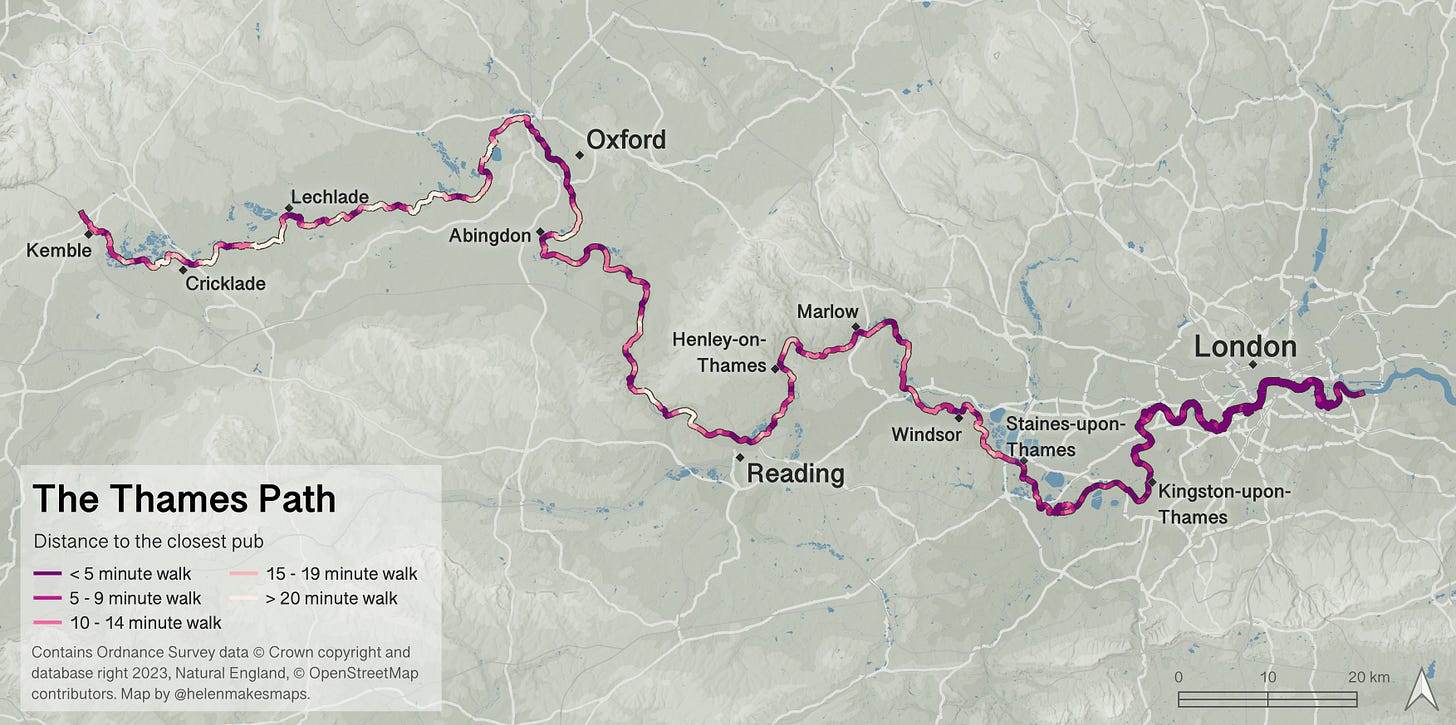

Thames Path pubs by Helen McKenzie

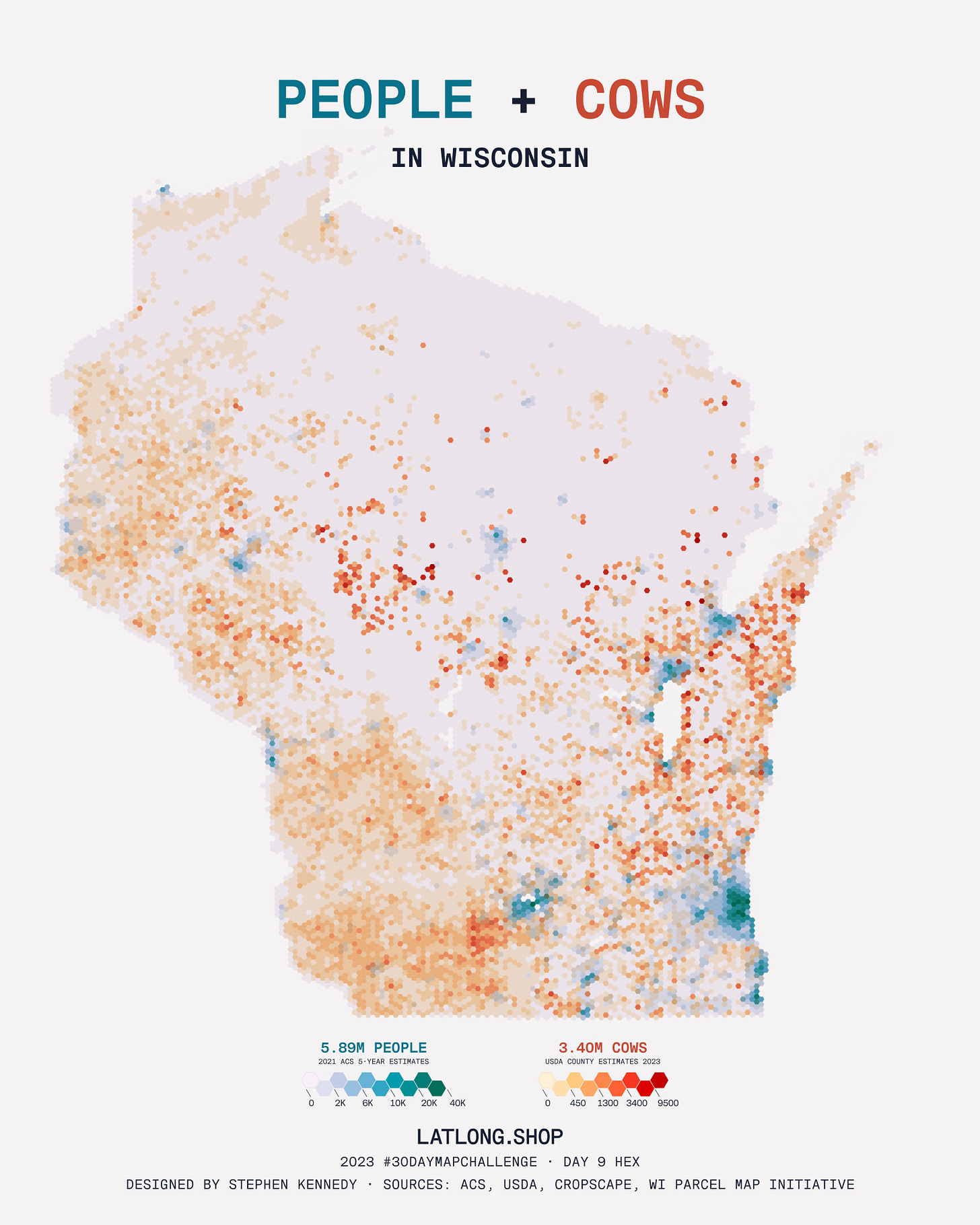

People and Cows in Wisconsin by Stephen Kennedy

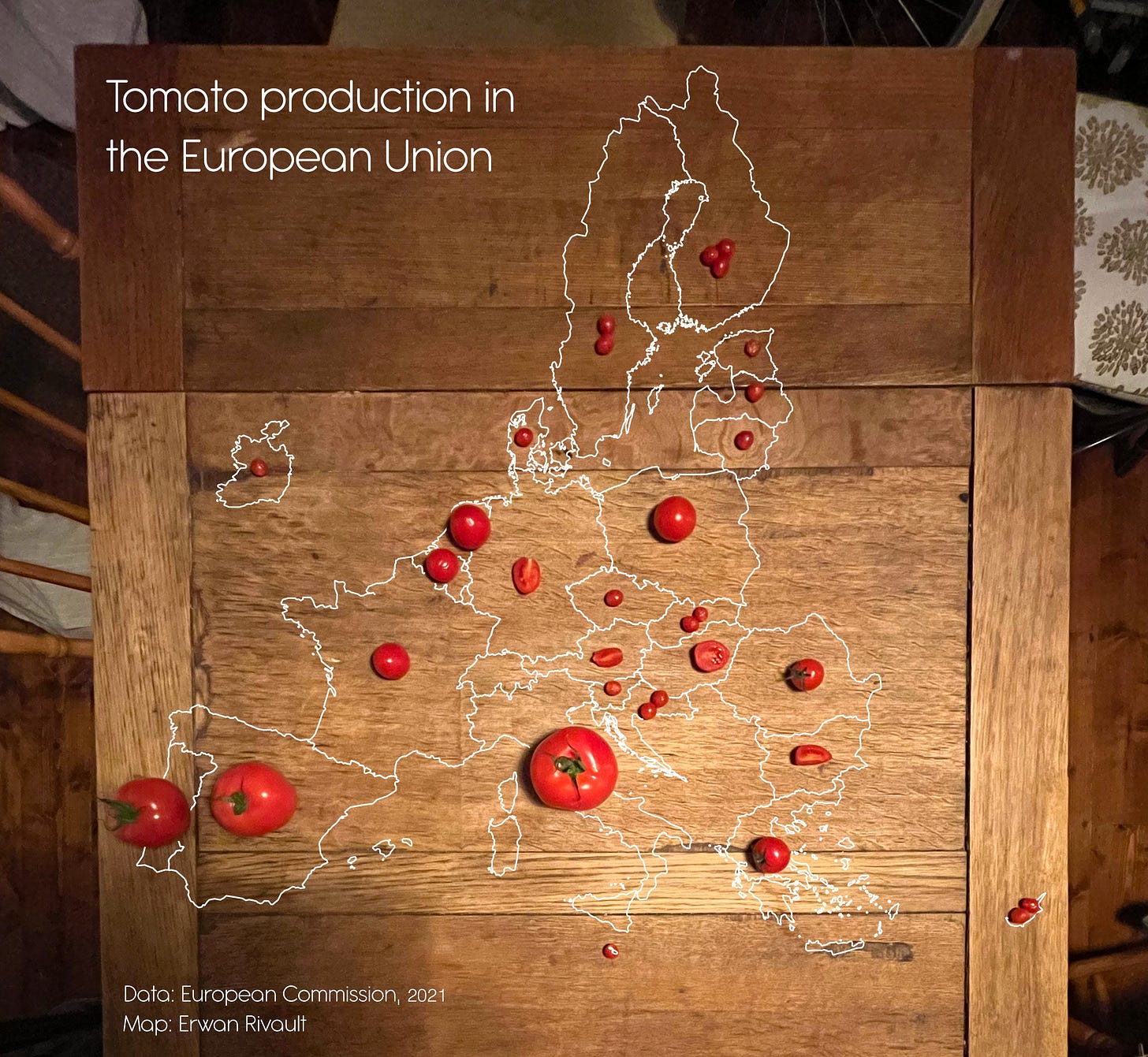

Tomato Production in the European Union by Erwan Rivault

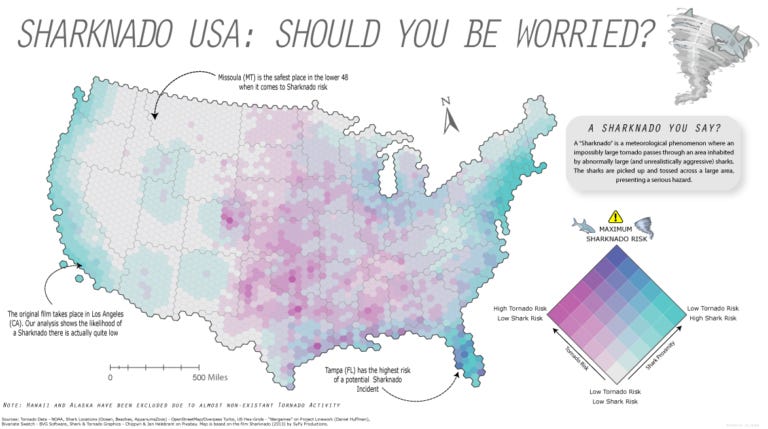

Sharknado Risk by Avenza Systems

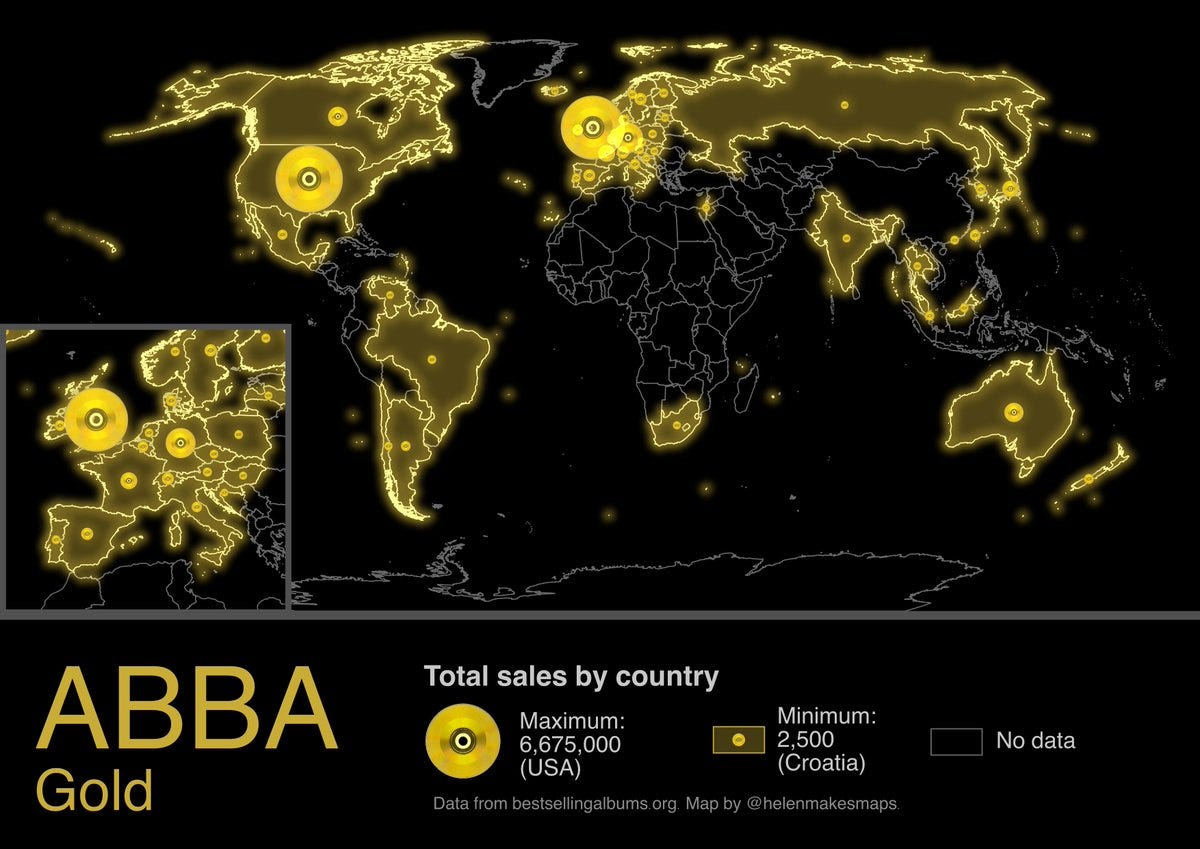

ABBA Gold sales by Helen McKenzie

Railways of Australia by the inevitable tterence (you may remember he also made these maps)

If you want more, the hashtag #30DayMapChallenge is your friend.

Thing 5 – Berglas

Not to make this a litany of inadequacy and failure, but magic is another thing I can’t do. Given that I have fallen some way short of the mythical 10,000 hours required to become proficient at something – 10,000 hours short, to be precise – this is no surprise.

David Berglas, who died last week at the age of 97, was good at magic. So good that he had an effect named after him. This interview from a couple of years ago offers a fascinating insight into the world of magic. It also features the interviewee getting shirty with the interviewer, which is always perversely entertaining.

And here’s the man himself explaining how he made a grand piano disappear.

Thing 6 – Saw

One of the more fun things I’ve done in recent months was delivering a 12-minute set on the link between the first bird, Archaeopteryx and the movie Top Gun: Maverick (it’s complicated) as part of the Festival of the Spoken Nerd’s Evening of Unnecessary Detail last month. (I’m not taking part in their next show, on 20th November, but it will be brilliant anyway).

On that last occasion, Steve Mould performed a routine in which he got fellow nerd Matt Parker to cut a plaster cast off his arm with a cast saw – not, you would think, an operation to be performed by an amateur, what with there being delicate human skin directly underneath.

Reader, I cowered. I feared. I trembled in anticipation of tragic headlines.

I should have known better. Steve is, above all, a professional.

Here he explains why a cast saw cuts through plaster but not through skin.

Steve’s video is delightful. I was thinking of trading in my Henson razor for a cast saw, but I guess now I won’t.

I think I would be a good hummingbird because my shoulders are hypermobile and I’m really, really good at getting sofas through small places. I don’t normally confess to being good at anything but my husband had to dismantle a sofa because he had no idea how I got it in. I’m pretty sure I read that properly and these are the only two skills I need to hummingbird