Thing 1 – Nightingales

What links the Max Planck Institute for Biological Intelligence and Italian composer Ottorino Respighi?

Come on, you know this one.

The answer is, obviously, nightingales. (I did slightly give it away with the title, didn’t I?)

Music lovers might well be familiar with Respighi’s 1924 work Pines of Rome, a magnificently unrestrained celebration of both the great city (where Respighi lived for twenty years) and the sonic possibilities of a stupidly large orchestra.

One thing Pines is notable for is its use of 6 ‘buccine’ – those circular Roman trumpets you might know from (among other places) the Asterix books.

I was delighted to discover this series of articles (and in particular this one about brass instruments, which features the buccine), exploring the painstaking attention to detail that underpins these wonderful books and makes them (whether the reader is conscious of it or not, and I certainly wasn’t) such a pleasure to read and reread, no matter what your age.

But I digress. This isn’t about brass instruments. It’s about nightingales. Focus, Parikian, focus.

The point is that Pines of Rome was a groundbreaking piece of music in one particular way: it was the first orchestral composition to incorporate a gramophone.

It’s deployed in just one passage (starting at at about 14’30" in the above recording). Its purpose? To play the song of a nightingale.

The gramophone (originally phonograph, of course) had been around for about 50 years by this time. It wasn’t the first sound recording device, though. That honour goes to the phonautograph, invented by Édouard-Léon Scott de Martinville, for whom let’s spare a thought, shall we? You can’t help but feel for someone who had a great idea but who languishes in obscurity because somebody else then did it better/faster/luckier.

The phonautograph predated Thomas Edison’s phonograph by some seventeen years. It was only ever intended to record traces of sound on paper, which de Martinville called ‘phonautograms’, the idea being that people would become as proficient at deciphering the squiggles as they were at reading. It was only in 2008 that the squiggles were converted to sound:

The idea of the phonautogram is recognisable to birders as the earliest predecessor of the sonogram, which is used by sound recordists to help with the identification of birds from their sound.

Here, for example, is the song of (guess who?) a (different) nightingale:

and here is the sonogram of the first ten seconds:

The nightingale of course brings us back to Respighi’s gramophone. With the benefit of hindsight it’s faintly surprising that the great musical developments made by composers in the early years of the twentieth century hadn’t seen fit to embrace this well established technology. Perhaps it needed someone with a flair for the theatrical to do it – the effect has been dismissed by many as ‘gimmicky’.

There are plenty of ideas floating around about why Respighi chose to use a gramophone in an orchestral work. People flex themselves into all sorts of contortions trying to make the link between the use of new technology and the rise of fascism, also citing the parallel between the march of the last movement ("Pines of the Appian Way") and Mussolini’s own march on Rome just two years earlier. You can read all about that, and much more, in this piece about music and timbre, which goes into a fair amount of fascinating detail about the nature of music and the music of nature.

Simplistic soul that I am, I prefer to think that Respighi liked writing pictorial music, wanted to portray the city he loved, and, as for the nightingale – and in his words –

“[I] simply realized that no combination of wind instruments could quite counterfeit the real bird’s song".

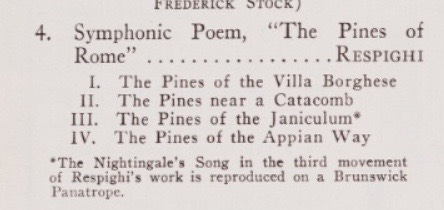

Anyway, one thing I’ve always wondered was how effective that gramophone recording might have been in early performances. I can’t seem to find reference to the exact model used in the world premiere, but here’s a clip from the brochure for the New York Philharmonic’s Stadium Season in 1926.

The apparatus in question was the very latest technology, and will have looked something like this

The orchestra’s relationship with the Brunswick company extended to a full page advertisement in the brochure.

"Electrical recording compares with mechanical recording as electric light compares to candle light"

Not that they were exclusive – there was also a lavish spread devoted to “the new ‘Universal’ model receivers” by Stromberg-Carlson. And when it came to pianos, the customer had a wealth of options: Knabe (“the most magnificent musical instrument of all time”), Sohmer (“there are more Sohmer pianos in use in greater New York than any other artistic make”), Steinway (“the instrument of the immortals”) and Baldwin (“choose your piano as the artists do”).

Which would you choose?

BUT I DIGRESS. SOMEBODY STOP ME.

As for Respighi’s bird, the romantic story is that the composer himself recorded the nightingale in the early morning at the very place portrayed in the score, Parco del Gianicolo.

This idea is quickly scotched by a glance at the score, which specifies “No. R.6105 del ‘Concert Record Gramophone’: il canto dell’usignolo” (“the song of the nightingale”). Confusingly, there are two such recordings, both made by pioneering sound recordist and canary breeder Karl Reich. The one from 1910 was the first commercially available wildlife recording, and the one from 1913 the second.

I’ll be starting rehearsals for Pines of Rome on Monday. In the good old days, you received a 78 rpm disc along with the orchestral parts. Progress is marvellous, of course, but the subsequent updating of the recording – first to a 33 rpm version, then a tape cassette, then a CD, and finally to a link to an MP3 – does somewhat suck the romance out of the whole affair. I try to reinject the romance with the thought that the sound we will be hearing is of a long-dead bird miraculously preserved in life through a succession of different media at the whim of an also long-dead composer .

Nightingales were hot in those days, what with the famous recordings made by cellist Beatrice Harrison a few months before the premiere of Respighi’s extravaganza. The revelation, a year ago, that the first of these recordings was in fact a duet between Harrison and a bird impressionist rather than an actual bird, dampened the magic just a bit. (The recordings became an annual event, and it seems that real nightingales were involved in those – it all raises questions of ‘authenticity’, which of course

BUT I DIGRESS.)

All the above was prompted by this research, undertaken by the Max Planck Institute for Biological Intelligence (you were wondering when I’d get round to it, weren’t you?), and the revelation that rival nightingales engage in 'song matching’, each bird impersonating the sounds just made by the other.

“Song matching requires the nightingale to adjust its song in real time to what it hears”

This film explains in a bit more detail.

Beyond the immediate ‘oh wow’ factor, there’s one thing about this I find particularly fascinating. It comes at about 2’15”. The nightingale, confronted with a synthetic whistling sound, starts singing in imitation. But its imitation isn’t quite perfect. It starts very slightly higher in pitch. Then, when the artificial sound stops and the bird is left to sing alone, it adjusts downwards and starts singing the exact pitch it’s just heard. But then, after a couple of seconds, its pitch goes lower just a bit, so it’s singing ever so slightly flat, as if it’s lost track of what it was imitating.

And of course there’s the usual sense of wonder at the abilities of non-human animals – what they do, how and why they do it – and just how much we still have to learn about them.

So there you go. Birds, eh? Cor.

Thing 2 – Insects

One of the highlights of our visit to the British Library’s ‘Art, Science & Sound’ exhibition a couple of weeks ago was discovering the extraordinary work of Levon Biss, whose insect photographs, taken at extremely high magnification, will (I hope) make you reassess your attitude towards the most abundant animals on the planet.

Here he is talking about it.

Thing 3 – Scream

We’re all familiar with the Wilhelm Scream, yes? No? Yes?

But do you know how to restore old tapes in bad condition?

Thing 4 – Moon

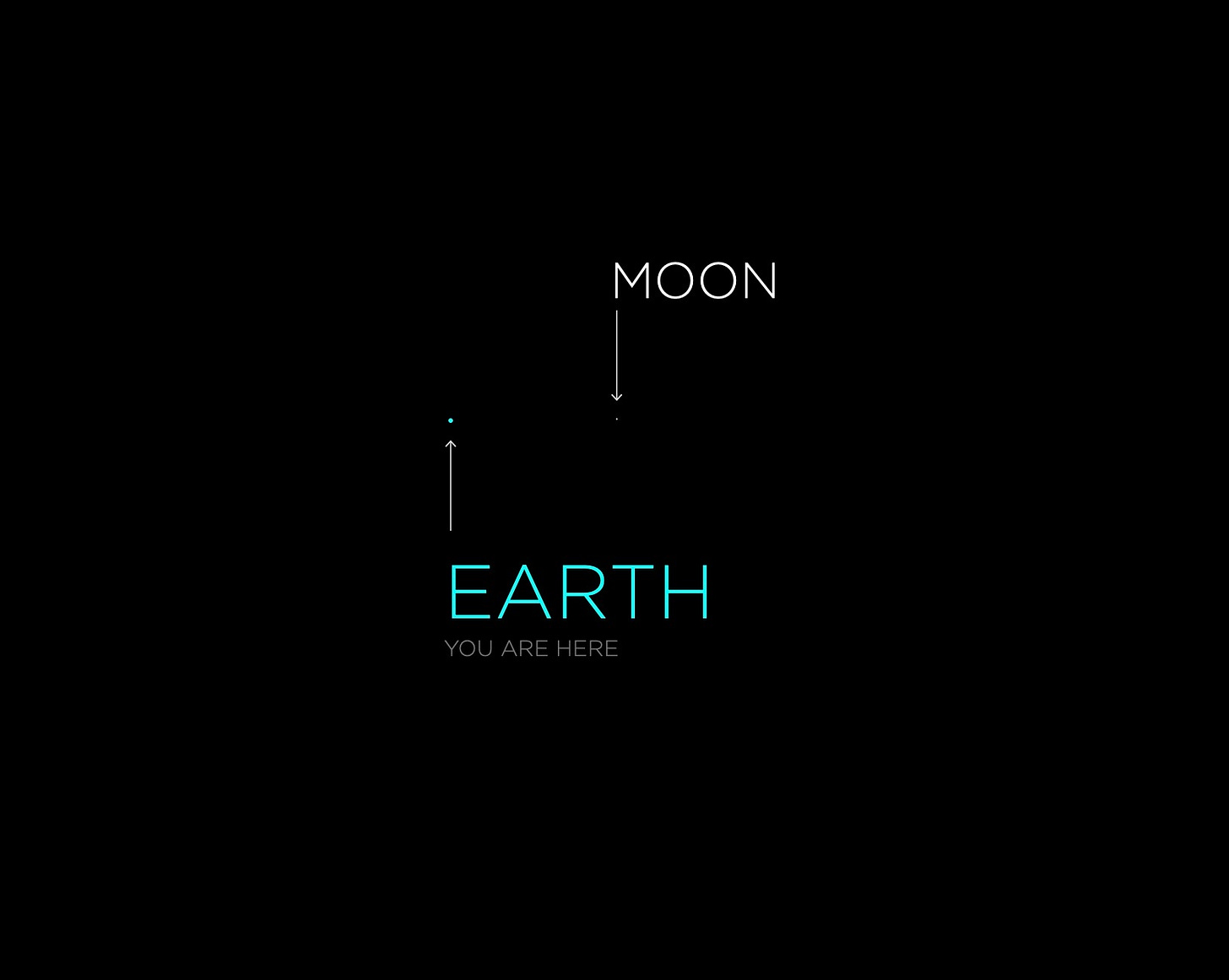

If the Moon is one pixel, what is everything else?

Thing 5 – Knots

Learn how to make ALL the knots.

This promises to be one of those resources that I say I will look at for five minutes every day (like the time I was going to learn BSL) and then basically completely ignore.

Thing 6 – Antipodes

Ever wondered where you would end up if you drilled through to the other side of the planet?

No?

Ah.

Well have a look at this antipodes map anyway.

I have very tired thumbs and I only got as far as Jupiter ...

Hours of fun!