Thing 1 – Mimicry

Alex was a parrot. But not just any old parrot. Alex was an African grey parrot who gained some notoriety thanks to his ability to – in the words of Irene Pepperberg, who devoted several years to training Alex and studying the results – “participate in some forms of inter-species communication”.

In short, he learned to talk. Crucially, he wasn’t merely repeating sounds, but identifying objects, colours and combinations of the two. You can read all about Alex here.

The uncanny vocal impersonation skills of captive birds is one thing, and the extent to which they can be trained offers a fascinating insight into ideas of non-human intelligence and exactly what we think it is.

But I’m even more drawn to the vocal mimicry observable in wild birds. The best known (in the UK, at least) are probably starlings, whose mimicry includes crying babies, V-1 bombs in WW2, aeroplanes, trimphones, referee’s whistles, and on and on. You name it, and a starling has probably impersonated it. I hold in my head the memory of standing in the village on Lindisfarne wondering where the hell that curlew was that I could hear singing. Eventually I looked up to the rooftop of a nearby cottage and saw that the curlew was in fact a starling. There is even a suggestion that these sounds are passed down through the generations.

Another famous mimic is the lyrebird. This footage, from David Attenborough’s The Life of Birds, has been widely shared.

It features a lyrebird imitating not just camera shutter clicks and whirs, but chainsaws. This has often been presented (including once by me, I confess) as “oh noes, it’s imitating the things that are destroying its habitat in the relentless march of destruction humans are wreaking on the natural world!”

It is true that humans are on a relentless m. of d. on the n. w. But apparently that particular lyrebird was a zoo bird, and under no threat from the chainsaws.

It just goes to show. I don’t know what it goes to show, but it just goes to show.

While those vocalisations are undeniably impressive and alluring, the crown for avian mimicry might just belong to the marsh warbler. They’re early learners, picking up sounds from the second month of their lives. And as long-distance migrants, flying to and from Africa every year, they have plenty of opportunities to pick up smatterings of song from a wide variety of birds on their travels.

Here’s a (long) recording of a marsh warbler including the impersonations of 57 identified (and more unidentified) birds. The stamina alone is worthy of respect. And given that the average human has a repertoire of three impressions, all of them terrible, it makes you think. I’m not exactly sure what it makes you think, but it definitely makes you think.

It might surprise you to learn – or it might not, as I have absolutely no idea what you do or don’t know – that blackbirds, renowned for the beauty of their song, are also in on the mimicry game, the pesky scamps.

Ours started singing last week, and most welcome it was, too, cutting through the gloom and drizzle to offer hope of something less gloomdrizzly just round the corner. There is a musicality to aspects of a blackbird’s song (I discussed birdsong and music in last week’s Six Things) which helps make it euphonious to our ears. I’ve recognised ours as the same bird each year because it would throw in the first line of ‘Camptown Races’ (although it drew the line at adding the ‘doo-dah’). This one does the same – almost. It stops after four notes. It also seems to have a smaller repertoire of tseeps, drurps and doo-waddas than ‘our’ usual bird, leading me to suspect that the old bird has gone the way of all flesh and that this one is its offspring. Birds add to their repertoire as they get older, and the average lifespan of a blackbird is between three and four years. The maths fits.

Bringing these themes together neatly is this footage, taken by Andy Marshall of the Genius Loci Digest (recommended, by the way), of a blackbird imitating police and ambulance sirens.

I’ve said it before, and I’ll say it again. Nature. Crikey.

Thing 2 – Ink

Sometimes all you want to watch is an old bloke kneading calligraphy ink dough with his bare feet. The rest of the film is fascinating, too.

Thing 3 – Alphabet

English pronunciation is undeniably illogical. There are several examples you can use to illustrate this. One of the commonest is the variation in treatment of the letter combination ‘ough’ in six very similar words: tough, trough, though, thought, through and thorough. And of course George Bernard Shaw demonstrated this illogicality by pointing out that the word ‘fish’ could equally be written ‘ghoti’ without any phonetic alteration. (If you don’t know it, or are struggling: the ‘gh’ is ‘f’ as in ‘trough’, the ‘o’ is ‘i’ as in ‘women’, and the ‘ti’ is ‘sh’ as in ‘nation’.)

Shaw proposed an alternative: it would have at least 40 letters, would be as phonetic as possible, and would consist entirely of symbols not found in the Latin alphabet. The idea didn’t bear fruit in his lifetime, but on his death in 1950 he left provision in his will for the establishment of a trust to create a ‘Proposed British Alphabet’. Even though the will was declared invalid after a lengthy legal wrangle, an out-of-court settlement was reached, and a prize offered to the best candidate.

In 1962, Ronald Kingsley Read (not to be confused with noted fascist John Kingsley Read) was declared the winner for his 48-letter Shavian Alphabet. Ironically, shortly before he died, he rejected the entire notion and devoted himself to a further alternative, now called Readspel.

The Shavian alphabet (a bit like Esperanto, I suspect, or any number of alternative musical notation systems) is one of those ideas that seems excellent in principle. Logical, consistent, easy to learn from scratch. How much better everyone’s lives would be if only we could all knuckle down and learn them.

One problem is that humans aren’t logical. And both systems suffer from the Catch-22 facing any alternative ‘constructed’ language or alphabet: few people are willing to devote time to learning something that is used by so few people, so gathering critical mass is an apparently never-ending process. Esperanto has 100,000 active users worldwide at the last count, which compares favourably to the 50-60 (not 50-60 thousand, to be clear – just 50-60) estimated to speak fluent Klingon, but is still a far cry from its intended use as the world’s universal second language. The Shavian alphabet, meanwhile, seems to exist mostly as a diverting intellectual and linguistic exercise. That’s a pity. Or, if you prefer, 𐑞𐑨𐑑𐑕 𐑩 𐑐𐑦𐑑𐑰.

If the idea of Shavian tickles your fancy, you can get started with this introductory video

And there’s all sorts of information on the official Shavian website, including links to books in Shavian by Austen, Conan Doyle and (strangely) Lovecraft.

Thing 4 – Pinocchio

I like it when science takes silly things seriously.

Here’s a paper examining how many lies Pinocchio could tell before it became lethal

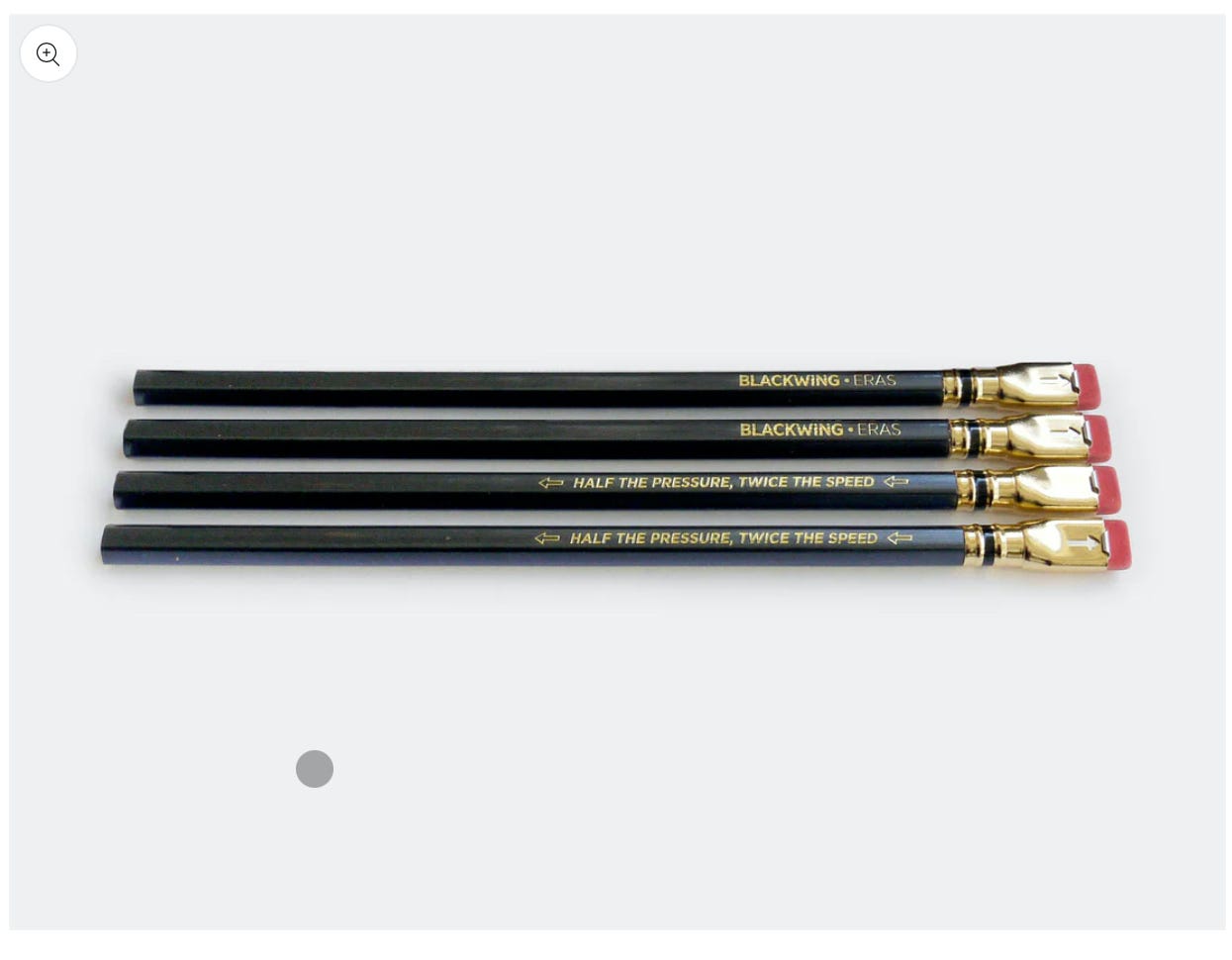

This comes courtesy of @presentcorrect on Twitter, a stationery shop dealing in addictive substances, for example these incredibly tempting Blackwing Era pencils (god but I do love a good pencil).

On which subject, Present & Correct did important work calculating the total cost of the pencils in Lydia Tàr’s stationery cupboard (I still haven’t seen the film, by the way, even though more people have now asked me if I’ve seen it than there are fluent Klingon-speakers)

Present & Correct have been on a roll recently, providing a link to:

Thing 5 – Inspiral

There is an online Spirograph.

(Stanley Tucci looking at butter voice)

Oh my gaaahhhd.

If you’re on mobile there’s an app.

Thing 6 – Pangea

Want to know where your home was 200 million years ago? Look no further.

Well done! My home was filled with music, and my parakeet was equally fluent in Bach and Brubeck. He learned Vivaldi violin sonatas from me. My father, a baritone, would shout Dutch curses at the parakeet when he (my father) was practicing Handel and the parakeet was trying out Vivaldi.

Fond memories of the blackbird who could imitate ambulance sirens. He lived in the grounds of HinchingBrooke Hospital.