This is the seventh of the mid-weekly posts sent to all those on the Birds list. If birds aren’t your thing, and all you want is the weekly Six Things emails, you can unsubscribe from these posts by going to the manage your subscription page. But do have a read anyway – you might find that birds are, after all, your thing. And if they are especially your thing, you can upgrade for £4 a month to access the second half of these emails.

Right, that’s the selling over with. On with the birds. Thanks for reading. This week I’ve recorded the first piece only. With two videos and the audio, the post might not load fully in your email, so just click on the heading or one of the videos to read/listen/watch on the web.

Murmurs

Nearly 59 years old and I’ve never been to Belfast. A parlous situation, belatedly rectified last week when I went there to talk about Taking Flight (have I mentioned it’s out in paperback in a couple of months?) to an enthusiastic and knowledgeable crowd at the NI Science Festival.

My interviewer, Conor McKinney, kindly suggested he show me a bit of the city before the event, so we duly met on a small patch of grass by the Albert Bridge on the River Lagan, and waited.

Not the usual city tour, you might agree, but when there are starlings around, other sightseeing opportunities are temporarily shelved.

What a thing. The billowing, the fluidity, the fffrrrreeeeooooo of thousands of wings beating in unison just a few metres above your head. I tried to follow the path of just one bird, but this soon proved impossible. It moved too fast, and my attention was always caught by something else or transfixed by the shape-shifting whole.

These spectacles have become an online staple in the last few years, but this in no way dilutes the gasp-inducing effect of experiencing one in the flesh – ‘ecstatic celestial gestures’, as Chloe Hope puts it with her usual grace and perspicacity. And even a smaller gathering engenders, as Melissa Harrison says in this excellent piece, ‘a quiet kind of joy’.

I didn’t have to share the video to social media, but dopamine is dopamine, so I did, and it inevitably proved popular. But while my edit captured the dramatic eruption of hundreds of birds from their resting position on top of a riverside building, equally fascinating to me was the quieter period just before. The collective swoop down, the splinter group that broke away off to the left, the jostling for position – budge up budge up, bugger off, I was here first – the ceaseless fidgeting.

We now have some idea of the science behind this behaviour – we know, for example, that the motion of each bird is dictated by the seven or so birds around it – but I would love to know more. What triggers the collective decision, about ten seconds in, to have a bit of a sit-down? What then prompts them all to curtail their tea break at the same time a couple of minutes later? When they settle down to roost for the night (under Albert Bridge in this instance), does each bird have its own established perch, like a pub regular, or is it first come first served? Do they hang out together in groups of family and friends, or do they mix with whoever they happen to be next to?

What are they saying?

Conor told me that the murmuration used to be larger, but had declined in recent years and then disappeared altogether. Light pollution seems to have been the culprit, but a campaign – led, as far as I can tell, by Conor, although he modestly deflected all praise – and healthy collaboration between conservationists and local authorities seem to have had a positive effect. The numbers we saw might not have been comparable to those of a decade ago, but the displays have been regular through this winter, which bodes well for their continuation next year.

It’s an eye-catching thing, a murmuration. Pedestrians stopped, craning their necks to get a better view. Behind us a small group formed, watching, filming, drinking it in. A bus slowed down – and not, as far as I could tell, because of traffic. And while some were oblivious, walking over the bridge without even an upward glance, they were in the minority.

A heartening experience all round, then. Not just the uplift from the birds themselves, although that would have been enough. But here is a positive story, an example of a relatively small and easy action that we can take which has benefits to the natural world and humans alike. Birds can become a source of pride in the community. ‘Our murmuration’, ‘our peregrines’. I gather from those closely involved with conservation that ‘community buy-in’ is the silver bullet. Persuade people to care and you can do anything.

Perhaps when people start saying – with a sense of pride rather than approbation – ‘our gulls’, we’ll know the battle’s been won. Until then, the struggle continues.

Flaco

On the subject of birds that capture the imagination, Flaco died.

You might not know about Flaco. He was a Eurasian eagle-owl from New York’s Central Park Zoo who escaped a year ago after the protective netting around his enclosure was cut by a vandal. Such was his fame that he had his own Wikipedia page.

Much of the online reaction to his death was, ahem, somewhat lacking in nuance. So it was good to see knowledgeable American Substackers coming to the rescue. Rather than contributing my own incoherent ramblings, I will merely point you towards Laura Erickson’s typically thoughtful and heartfelt appraisal and ryan mandelbirder’s excellent ‘i have a take too’ – in it he links to Barry Pechetsky’s fine assessment.

Hummingbirds

I still haven’t forgiven The Americas for hogging the hummingbirds. But each year I swallow my pride and turn at least part of my attention westwards to monitor their progress from South America to North.

A lot of bird migration takes place at night, but hummingbirds buck the trend, moving during the day to take advantage of nectar availability en route. The thought of these tiny things undertaking huge and hazardous journeys every year is both awe-inspiring and ever so slightly befuddling. And the more we learn about these journeys – not just hummingbirds, of course, but thousands of other species all over the world – the more extraordinary they seem.

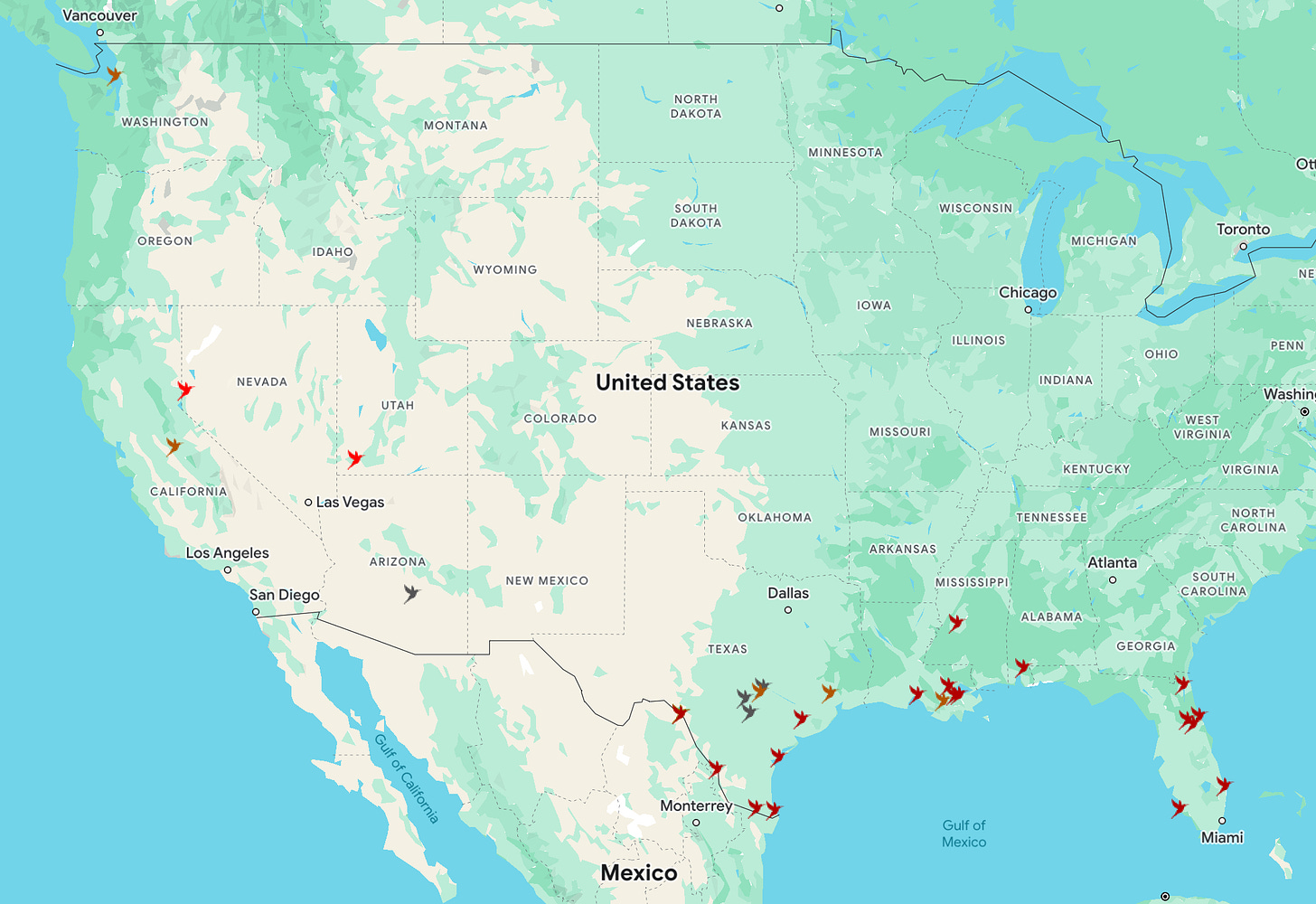

This is the state of play as of even date.

Early days yet, of course. Expect it to fill out significantly in coming months – the ruby-throats (dark red) will densely populate the east, while a variety of other species will fill in the west. Here’s last year’s to see what you might expect.

Thanks for reading. That might well be quite enough bird talk for you. If it isn’t, below is a short thing about swallows and martins and swifts.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Six Things to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.