This is the fourth of the mid-weekly posts sent to all those on the Birds list. It’s rather long, so your email programme might not load it all – just click through the heading to read it on the website.

If birds aren’t your thing, you can unsubscribe from these posts by going to the manage your subscription page. But do have a read anyway – you might find that birds are, after all, your thing. And if they are especially your thing, you can upgrade for £4 a month to access the second half of these emails.

Right, that’s the selling over with. On with the birds. Thanks for reading. This week there are audio versions of both parts of the post.

You’ve Been Gulled

Pity the gull.

And immediately, just three words in, I’ve lost some of you.

Pity the gull? I think not! I love birds, but I have my limits. They’re a scourge. Delinquents. Scoundrels. Despicable nee’er-do-wells to be reviled and rejected. Good day, Sir. I SAID GOOD DAY.

But wait. Let me plead their case.

You probably know the gulls I’m talking about. You might call them ‘seagulls’. This, by the way, is a word I’m perfectly fine with, much to the annoyance of pedants, who will insist that ‘there is no such thing as a seagull’. Well, no, there isn’t. But we all know, roughly, what is meant by the word. You can, if you want, go into more detail, citing the differences between great black-backed, lesser black-backed, herring, black-headed and so forth. And I’d be happy to go along with you on that particular journey, because each species is worth exploring in its own right, with their own characteristics and foibles. And, contrary to what many people might tell you, there is beauty in them thar birds. Look at the beaky nobility of this dude (a juvenile herring gull, doing his best to recreate this iconic photograph of John Gielgud.

But if you’re a gull agnostic and all you want is a catch-all word to describe the members of the family Laridae, then ‘seagull’ will do fine. I prefer ‘gull’, but I also prefer dark chocolate to the milk variety. It doesn’t make me better than you.

ANYWAY.

Gulls. Gulls gulls gulls.

Let’s take, as the representative bird, familiar to most people, the herring gull. Larus argentatus.

Adam Nicolson has this nice description of them in The Seabird’s Cry.

“a cartoon of small-town criminality… respectable citizens on the pavements; louche parasites loitering above them. If birds could chew gum, these would be.”

Few birds meet with such disdain.

Shrieking hooligans!

Perhaps. Or you might prefer to recall the words of Mark Cocker, in Birds Britannica

“Herring gull notes have a decidedly human quality and often a strong, deeply ambiguous charge, sounding almost exactly halfway between manic laughter and an empty, despairing wail.”

But they’re taking over!

Easy enough to think so, but no. No, they’re not. You might think they are, because they’ve shifted into urban areas in the last few decades, so you might see them more often than you used to if that’s where you hang out, but it’s an illusion. The herring gull population in Britain has undergone a steady decline since its peak in the 1970s, to such an extent that they are now on the Red List of Conservation Concern.

The bastards stole my chips!

Yes, because THEY’RE CHIPS and YOU WERE EATING THEM IN PLAIN SIGHT. What did you expect the gull to do? That’s free food right there, and you weren’t fast or canny enough to stop them.

And relax.

For the sake of balance, I should acknowledge a couple of things. Yes, a family of herring gulls outside your bedroom at four in the morning is vexing. If I were subjected to that noise at close quarters on a daily basis no doubt it would affect my view of the birds. Proximity can do that.

And as they are a roof-nesting bird (possibly the first to adapt to this opportunity) this can mean severe inconvenience for residents of those buildings, including aggressive attacks by birds in breeding season, when they perceive humans as a threat to their eggs and young. Not much fun for those in the firing line.

Furthermore, while their population has declined sharply in coastal areas, they’ve moved inland, and especially into city centres, where they can gather in large groups. Too many of any animal is, well… too many. I love the golden eagle, that noble epitome of rugged majesty, occasionally glimpsed soaring over the Scottish Highlands. Do I want fifty of them crapping on my West Norwood patio? I do not.

It’s the usual story. We like the natural world to keep its distance. When it encroaches, becomes a nuisance, then we have a problem.

But it’s a problem of our own making. Adam Nicolson again:

“[a study found] that birds feeding on human rubbish laid fewer eggs, had fewer live chicks per clutch and fewer survivors from those that did hatch. A junk diet was making junk birds. It’s a disturbing realisation: the gulls on the Hastings seafront, largely fed on fish and chips and on the rubbish from people’s bins, have been transformed by the food we have been giving them. They are no longer wild creatures, but a reflection of who we are and how we live. They are the gulls of the Anthropocene. The impression you get, the instinctive gut feel of these birds on the seafront, that they are somehow degraded and impoverished, is borne out by the science. We have created a race of gulls that reflects the worst of us.”

There is much to admire in herring gulls. They are canny, adaptable and opportunistic. It’s not just the chip-nicking. Mark Cocker again:

“Their diet is gloriously catholic, extending to rope, bonfire charcoal, matchboxes, greaseproof paper and the rubber seals around car sun-roofs.”

And while our activities have contributed to their decline, for a while there we were doing them some good. When the 1956 Clean Air Act banned the burning of waste at rubbish tips, the conditions were laid for gulls to proliferate – landfill sites remain prime locations for gull watchers. Industrial fishing played its part, too, with copious amounts of food thrown overboard – easy pickings. Eric Cantona understood this, even if I bridle at his comparison of these noble birds with journalists.

Their reputation as chip-nickers is well earned, but sometimes you meet a gull that is more circumspect. This juvenile was perhaps too young to understand that asking politely doesn’t always yield results.

If you’ve ever fallen prey to gull-induced chip theft, my earlier disdain for your misfortune might sting, so if it makes you feel better, it’s not just humans who fall for it. Worms are gullible (YES, PUN INTENDED – WHY DO PEOPLE SAY ‘NO PUN INTENDED’ WHEN IT QUITE CLEARLY IS?’) too. One of my favourite of all bird behaviours was highlighted by all-round good chap and Everything Is Amazing substacker Mike Sowden (highly recommended, by the way, but on absolutely no account must you tell him I said so).

For all that it looks as if this gull is perfecting its audition routine for Riverdance, it is in fact perpetrating an expert confidence trick on earthworms. The stamping routine mimics, as near as dammit, the sound of raindrops on the ground.

“Aha!” think the worms (and other invertebrates), “it’s raining! We must hasten surfacewards (for reasons that still remain a mystery to humans).”

Up go the worms (and other invertebrates), straight into the waiting beaks of the gulls. This behaviour, known as ‘worm charming’, is both comical and fascinating, the sweet spot for nature-related factoids.

Wherever you live, it’s likely you’ll see a gull in the next few days.

Perhaps it’ll be floating over your garden on outstretched wings, exploiting the air currents with an ease we can only envy.

Perhaps it’ll be fixing you with its piercing eye, demanding food.

Perhaps it’ll be tap-dancing a worm to death.

However you encounter it, just remember that it’s only doing it’s best to get by, and if that means patrolling the pavement outside Gregg’s until a hapless punter leaves a corner of doughnut exposed, then so be it.

Gull Corner

My thanks to Helen for sending me this excellent story about gulls in London.

I wrote a short thing for The Guardian about gulls.

You won’t find a more eloquent advocate for gulls than Tim Dee. His masterful short book, Landfill, is a must for any gull-admirer.

That’s Enough Gulls, What About Owls

Talking of worms and birds, here’s a thing.

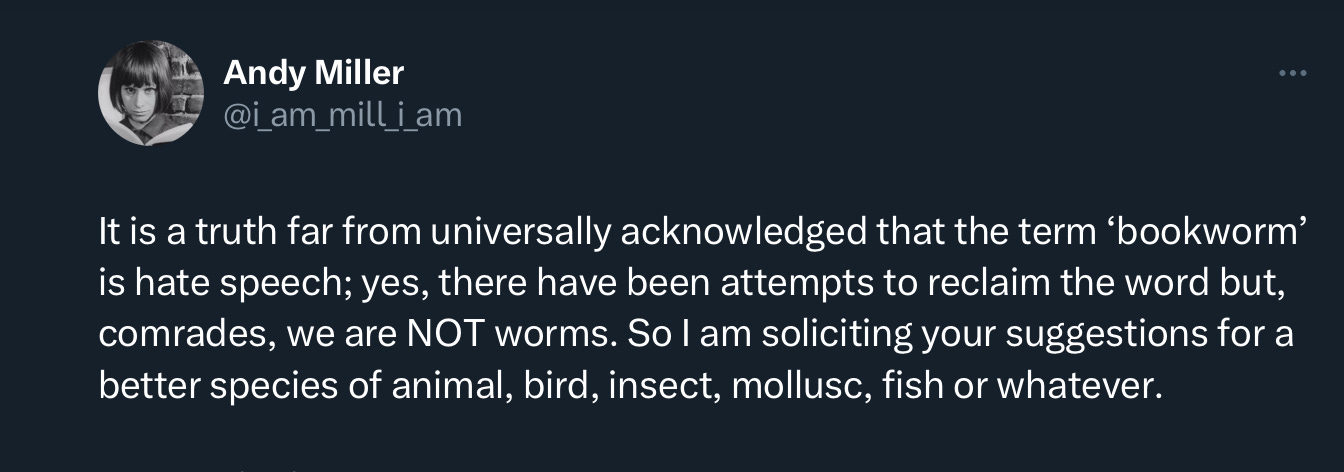

Tiring of the word ‘bookworm’, Andy Miller (author of The Year of Reading Dangerously and presenter of peerless book podcast Backlisted), decided change was long overdue. And when you crave change, what do you do?

That’s right. You start a Twitter poll.

To ensure a fair process, Andy first canvassed opinion, then presented the suggested options to the public.

They were:

Bookworm 🪱

Bookwyrm 🐉

Bookowl 🦉

Bookpig 🐖

Inevitably, I felt the need to make my mark on proceedings.

At first it looked as if my influence would be entirely negative, bookowl’s share of the voting decreasing from 34% (1st place) to 31% (2nd place). But eventually people got the message, and it took back the lead, only yielding to a late surge from the traditionalists.

The final result might just be the ideal outcome, giving both traditionalists and owl fans what they wanted.

Thanks for reading. That might well be quite enough bird talk for you. If it isn’t, below the fold this week we have six birds that don’t exist but darn well should.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Six Things to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.